War

When the low flying Indian planes started bombing the petroleum dumps at Karachi Port in December 1971 and smoke covered part of Karachi, two Bengalis and a Canadian working at Oxford University Press came with their English boss, Martin Pick, to live with us, as the climate of hysteria that was building up against Bengalis and foreigners made it unsafe for them to live on their own. A bomb fell on the house of Shaukat Fancy, destroying part of it, but Shaukat and his wife were safe. The Canadian used to get hysterical at the sound of sirens when we had to observe strict blackouts and went into a safe room under the stairs. He used to say that, ‘It is not my war. Why am I here?’. His government soon evacuated him to Canada. The other three stayed with us till things calmed down, and enjoyed being with artists, who continued to come in the evening to work at our art gallery. One of the Bengalis went on to set up a publishing company in Bangladesh. And Martin Pick went back to England to set up his own publishing company and manage his father’s publishing interests.

Yasmeen Lari was asked to prepare the plan to reconstruct the area that had been occupied by the Indians in Shakargarh and Tharparkar. She was expecting therefore I would be one of the first civilians to document the area when the Indians vacated it. She was against turning people into beggars by distributing money and goods among them. She believed that people in villages traditionally built their houses therefore they should be helped by being paid for the work they did to rebuild their houses according to her design. I proposed that all landless persons living in the villages must get at least five marlas of land on which to build their homes, otherwise many villagers especially skilled (kammi), who were getting good money for their skills in the city, would not return to be again at the mercy of their landlords. Mr. Bhutto accepted both our proposals. The bureaucrats did not like our direct dealing with the politicians in power, so our old friend Mukhtar Masood, the secretary of the planning commission, sent us a telegram for our plan of action. I knew the tactics, therefore I telegraphed back, ‘Time for action no time for plan of action’, but it was of no avail. The local politicians and the bureaucracy wanted money in their hands and they had their way led by Masroor Hasan Khan, Punjab Secretary for Rehabilitation.

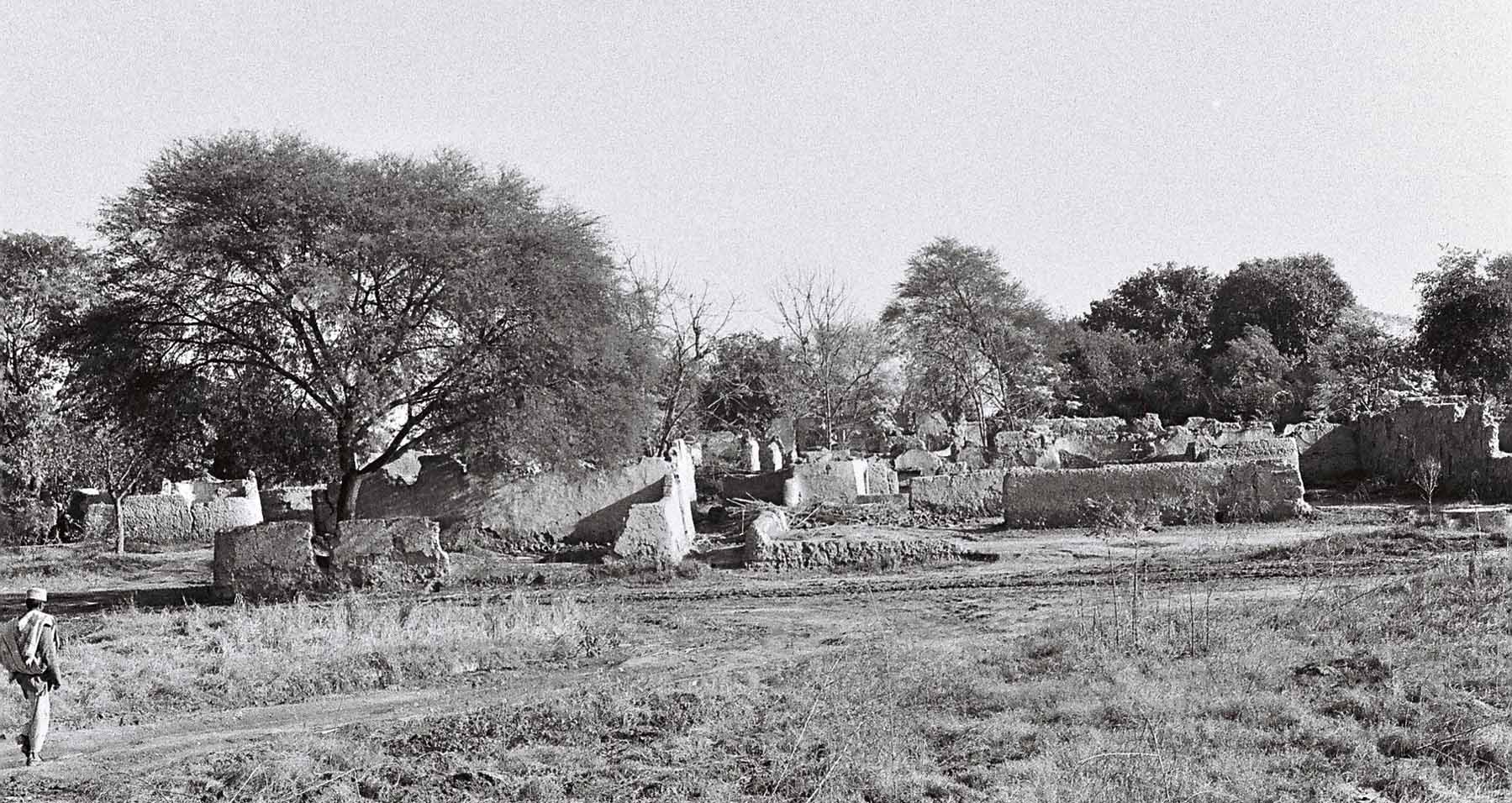

The area occupied by the Indians was totally ruined, with nothing left except crumbling mud walls. All the windows, doors, roofs and every kind of woodwork had gone, burnt to keep the Indian soldiers warm. All the wells had been filled with muck. The only sign that there was ever sweet water in Tharparkar, was the birds that hovered over it, or sat there rubbing the ground with their beaks. However, there were some parts of Tharparkar where Hindu inhabitants had stayed on, and therefore these parts were intact.

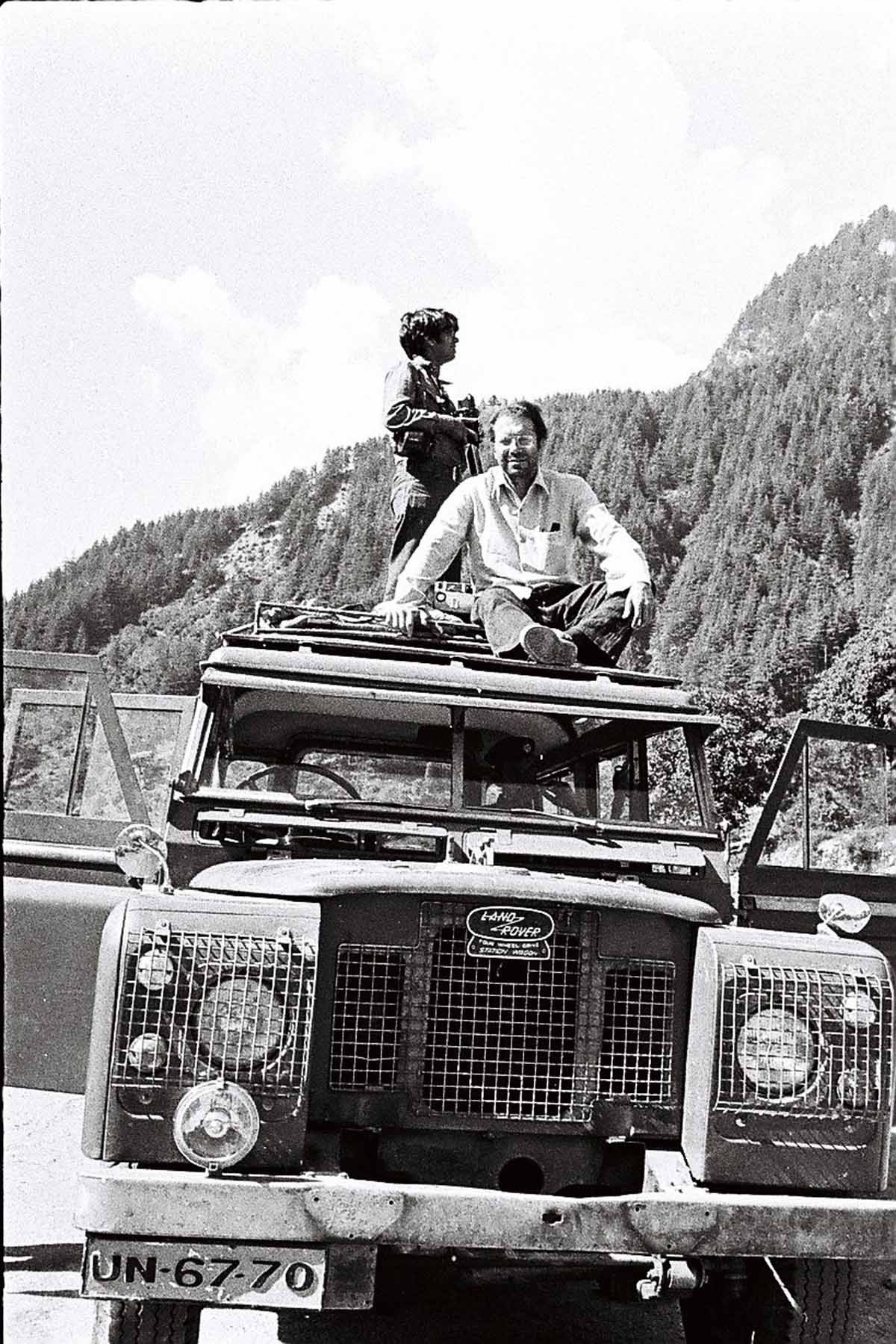

One day a Swiss gentlemen whom we had never met entered our house, with a copy of Hamid Zaman’s full page article in the ‘Morning News’ on Yasmeen Lari’s plan for villages in war-affected areas. He wanted her to build a mud house for him. I explained to him that we ourselves wanted to build a mud house in Defence where we lived, but the building laws did not allow us to do so. However he did not leave. He had just retired as head of Sandoz, a Swiss pharmaceutical company, and was waiting for appointment as the head of UNICEF in Pakistan. He decided to spend the months of waiting for his appointment with us, because he wanted to see Pakistan with us while we documented its heritage. When his son came for holidays we went together with my son, who also had holidays, in his Land Rover. My son Mihail and I photographed, while he and his son collected handicrafts from Thar and woodwork from Swat, which they sent from Peshawar by truck to an ethnological museum in Switzerland. When George Gogol became head of UNICEF in Islamabad with the status of an ambassador, he decided to live in a village in a mud house, instead of his official residence in Islamabad.

When the floods of 1972 came, he asked me to prepare a report and film of the affected areas for UNICEF. I took with me, Dawood Subhani, the ‘Time’ photographer, and one of the best photojournalists that Pakistan has produced. While I photographed he filmed Punjab and Sindh from Sialkot to Thatta, travelling in a range rover provided by UNICEF and driven by Sindhi landlord Sanjrani because of his driving skill and knowledge of geography.

Dawood was a tall man with long legs, who had a habit of suddenly veering off in any direction, and expecting his companions to search for him and join him in whatever he had decided to do. I could not believe it when one day I found that he had married and settled down with children. But I was not surprised when I found that his wife and children had left him and gone to America. I had not kept pace with him, as Dawood liked to be where the action was, with a bullet still lodged in his thigh since the student movement of the 1950s. It is a pity that he did not take care of his diabetes, and died young due to an untended toe injury, which proved fatal. One does not know what happened to his wonderful collection of negatives and slides, because apart from his professional assignment he was generous about taking photographs of people he knew. For example he took photographs of my wedding, to which he was not even invited because we had just arrived from UK and we did not have his address. But he always kept his ear to the ground. He had a wonderful way of becoming friendly with everyone, and sensing interesting events in their lives. I would like someone to locate his work and save it, as it is a record of a very interesting period of Pakistan’s history. I wish he were still alive and photographing. I miss him.