East Pakistan

Patricia Clements was a British writer of a series of children’s books published by Oxford University Press for schools, called “Ahmed and Rehana”. She lived on the Isle of Wight in a house covered with green creepers and surrounded by beautiful shrubs and trees. She drove to Pakistan every winter with a friend who dropped her in Pakistan and went on to India, where he had a teaching assignment for the winter.

At that time there was a restriction on taking foreign exchange out of the country, therefore Pat spent the royalties from her books in Pakistan by celebrating her birthday in orphanages, and buying gifts for their inmates. She also lectured teachers on how to teach English and hosted a ten-course Chinese dinner for her friends at the ABC restaurant on Elphinstone Street (now Zaibunnissa), beginning and ending with green tea.

When Pat asked me to go with her to East Pakistan, I agreed readily, as I had an agenda of my own which was to attend the opening session of the newly elected parliament. Before that we went to see Raja Tridev Roy, who was one of the two to win election against the tidal wave unleashed by Sheikh Mujibur Rehman in East Pakistan. Tridev Roy was raja and religious leader of the Chakmas, who are Tibeto-Burman and Buddhist as opposed to Bengalis who are mostly Aryan and Muslim. Raja took us on a houseboat to see his tribe in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, and to show us how Kaptai Lake had submerged the best Chakma land and their ancestral homes. We were accompanied by the Chakma member of the provincial assembly who was very emotional, and started to cry whenever he described the condition of his people and the way they had been treated by the Bengalis. During the 1971 war Raja Tridev Roy sided with Pakistan, and after the independence of Bangladesh he remained in Pakistan, and became a federal minister and later ambassador to Argentina. He published his memoirs, entitled ‘The Departed Melody’.

After my British friend left I decided to move to Governor’s House in the hope of seeing the new Parliament meet in Dacca. But when I arrived in Dacca on 1st March 1971 and stepped into the office of the Military Secretary of the Governor of East Pakistan, I heard Radio Pakistan announcing in the one o‘clock news that the National Assembly would not meet on 3rd March. At lunch I decided to go back to Karachi, and asked the wife of the military secretary to help me with shopping. But when I went upstairs to my room to change, I saw smoke rising in the distance, and informed the military secretary of what I had seen. He immediately got on the phone and confirmed my worst fears. East Pakistan was in revolt. That afternoon the governor resigned, and at night one could hear firing around Governor’s House. The Bengali ADC told me with tears rolling down his cheeks that they were killing Bengalis, while the Punjabi colonel claimed that they were only firing in the air. However, by next day peace had been restored as the army had retreated to the cantonment, and Awami League volunteers had taken over Dhaka.

On that day an unfortunate thing happened to Iqbal Rasheed Siddiqui. A number of Bengali boys were playing in his house. One of them had a gun, which accidently went off and killed another Bengali boy. The rumour spread that a Punjabi had killed a Bengali, and a mob ransacked his house despite the fact that the dead boy’s father stood there saying that this was not the case. But the crowd said that he had gone off his mind because of the shock of the death of his son. However Iqbal’s wife and children were able to take shelter in the house of British diplomats. Iqbal himself jumped over the fence to find refuge with the neighbour’s gardener, who locked his quarter from the outside to give the impression that there was no one there. Many months later I found Iqbal on I.I. Chundrigar Road in Karachi’s financial district. He told me that he had become a refugee a second time and was now looking for a place to start a new business. I took him to my office on 7th and 8th floor in Muhammadi House and gave him two rooms and a telephone, and told him that he was free to use them till he had managed to establish his business.

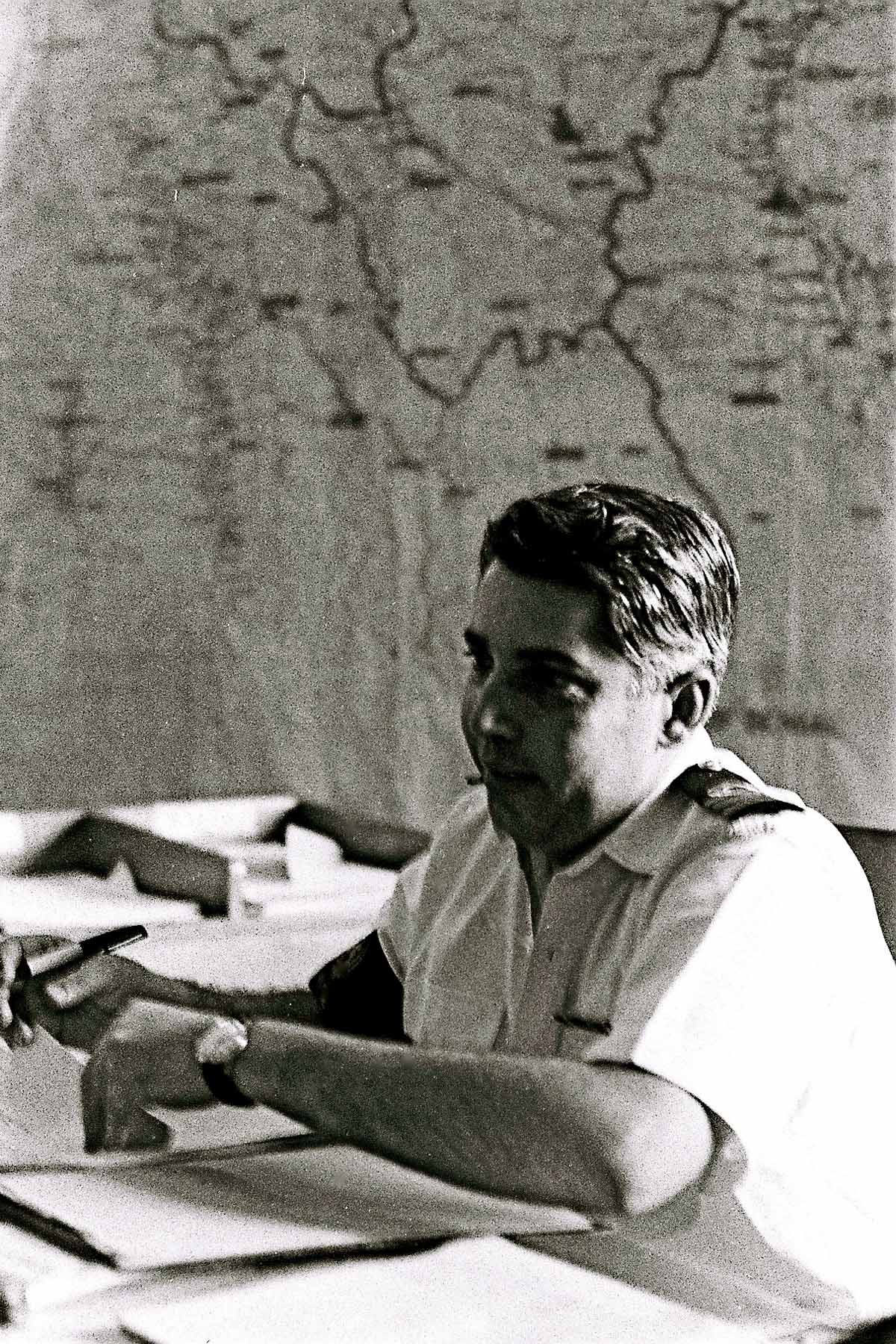

When I cancelled my shopping with the wife of military secretary the Punjabi brigadier had told me to be brave and go out, as when they saw a west Pakistani the cowards would give way. Now, I was the only non-Bengali who ventured out of Governor’s House in my khaddar kurta and pajama with my Bengali friends. When I returned on the fourth day, Admiral Ahsan was anxiously waiting for me, as a helicopter had arrived to evacuate us to General Yaqub’s place in the cantonment where Ahsan had a meeting with Yaqub. We were later transported to the airport for a PIA flight to Karachi via Colombo. That evening a top-secret signal from Yaqub to Yahya was sent. It said, ‘A military situation would lead to large-scale killings of innocent civilians; it would not help in achieving the aim. It could, on the other hand, lead to catastrophic consequences. I cannot accept a mission, which would prove disastrous. I, therefore, hereby offer my resignation’.

It was an act of great moral strength for Sahebzada Yaqub to give up a brilliant army career at the age of 50, rather than carry out orders of his superiors contrary to his belief. He was proved correct when Pakistan lost East Pakistan after the unnecessary massacre of civilians by both sides, and suffered a humiliating defeat in both East as well as West Pakistan. We lost the whole of East Pakistan and lost over five hundred towns and villages in Shakargarh and over fifteen hundred towns and villages in Tharparkar, in West Pakistan.

When I was leaving for East Pakistan, Mustafa Khar had brought packets for me to deliver to Kaisar Rashid, who was personal secretary of Mr. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto when he was foreign minister. Now Dr. Mubashir Hasan came to learn about the situation in East Pakistan. When I told him that hundreds of Bengalis had been killed, and that thousands of them were prepared to die, he replied that lakhs had laid down their lives for the creation of Pakistan, so we could sacrifice few thousands more to save the country. It reminded me of the 1965 war with India when Pakistan had sent volunteers into Kashmir to snatch it from India and had failed. However, the Pakistan Air Force, trained and equipped by Americans for CENTO and SEATO, to fight the Communist incursion from the north, was used against the Indians, with great effect. When the Americans objected we hated them, and continue to hate them because the success of the Pakistan Air Force had galvanized Pakistanis into the belief that we could have beaten the Indians but for betrayal by the Americans, who had failed to continue to provide us military supplies and equipment. Kaiser Rashid told me that when the Indians attacked the Pakistan border in retaliation to our incursion in Kashmir in 1965, he was with Bhutto in a car on the way to a meeting at the President’s House and that on the way Bhutto said that he would now like to see how Ayub survives.

In 1971, Bhutto convinced the generals that the Awami League would adopt a conciliatory attitude towards India, relegate Kashmir to the back burner and direct funds from defence to the economic development of East Pakistan. Meanwhile the bureaucracy was afraid that Bengali representation in various government departments and autonomous agencies would be increased with no regard to merit, qualification or seniority. And there were economists who were bewitched by American economic historian Walt Whitman Rostow (1916-2003), who had come out with a non-communist manifesto in 1960, which propounded theories of the stages of economic growth and take-off. They believed that East Pakistan was an economic burden and that without it Pakistan would reach the takeoff stage earlier.

They were mistaken, because Rostow was an American who was not aware of the West Pakistani mindset, which was entrenched with reaction and feudalism by its founding father (chapter 5), and later by Bhutto, who held summit of Islamic countries, nationalized major native industry, education and enterprise.

‘Yar aghyar ho gay hayn

Aur aghyar musir hayn kay who sab

Yar ghar ho gay

Ab koi nadim ba safa nahin hay

Sab rind shrab khawar ho gay hayn’

Faiz Ahmad Faiz