Slums

General Muhammad Azam Khan (1908-1994) was appointed the Refugee Rehabilitation Minister by the martial law government in order to clear the centre of Karachi of refugees who had been squatting there since partition. He came to Karachi University to ask students to help him to identify slums and prepare a list of squatters. I was leader of a group of these students. We were paid the princely sum of ten rupees a day for transport and food. In those days you could have a plate of curry and huge paper-thin rumali rotis for four annas in the Irani restaurants, which dotted most of the famous street corners of Karachi. I came across many educated refugee families who had been living in jhuggis in pitiable conditions with their families in the slums since independence. Later that year I went to study abroad while General Azam got houses built for the refugees in Korangi and shifted them there.

When I came back in 1963 I decided to find out more about slum dwellers. I prepared a detailed questionnaire and employed two female students from the sociology Department of Karachi University to conduct an in-depth study of people living in the slums on the basis of my questionnaire. I found that a large number of people who had been shifted to Korangi away from their places of work by the martial law regime, could not keep their jobs or afford the daily cost of transport. Therefore they had come back and created new slums near their places of work in the city. I also found that Karachi was inhabited by many interesting communities. For example, one poor community living in jhuggis next to a rich housing society never cooked at home, as both men and women went out to work for the day. Therefore they got their food from neighbourhood eateries, where the whole family including children went to eat whenever they felt hungry.

Fortunately my wife, Yasmeen Lari, was not only the first female architect of Pakistan but also one of the few fully qualified architects in Pakistan, having done a full five-year course in architecture approved by the Royal Institute of British Architects. After qualifying from the U.K., she designed the largest chemical factory for Pakistan in Germany. And in Pakistan she was chief architect of MacDonald, Layton and Costain, which at that time constructed major industrial projects. She also taught at the School of Architecture, which held classes in the evening.

UN experts who had been asked to prepare the master plan for Karachi asked her to assist them. My wife proposed that instead of driving them away again, people living in slums should be settled where they had squatted near their places of work, by the use of her design ideas. It was a radical idea, which breached all the norms of old fashioned planning. She met immediate opposition from the well-entrenched bureaucracy in KDA and the Government of Sindh. However, she had her way, as the Ayub government fell and the whizz-kids of Air Marshal Nur Khan, as old bureaucrats derisively called his young advisers, were like her, recently returned after being educated abroad, and one of them was her brother. The Secretary of Finance, Ghulam Ishaque Khan, opposed it tooth and nail in the joint meeting of two of the trio in power, namely Air Marshal Nur Khan and Admiral S. M. Ahsan, who held all the civilian ministries between them. She defended her ideas vociferously, and the admiral appeared to side with his secretary of finance, Ghulam Ishaque Khan, till a wink from him made her realize that he would in the end support her proposal. The admiral allocated a substantial initial amount towards slum up gradation. Our friendship with the admiral paid off. So did my wife’s London relationship with the whizz-kids of the air marshal. She was also asked to prepare a report on slums by the government of Pakistan. Dr. Mubashir Hassan (later Finance Minister in the first PPP government) and I helped her with this. She flew to East Pakistan to investigate conditions there where the first Bengali Chief Secretary of East Pakistan, Shafi-al-Azam, who had worked under her father helped her, and Khalil Umar put her up; while I documented the slums in Karachi, and Dr. Mubashir Hassan did an analysis of the Punjab situation.

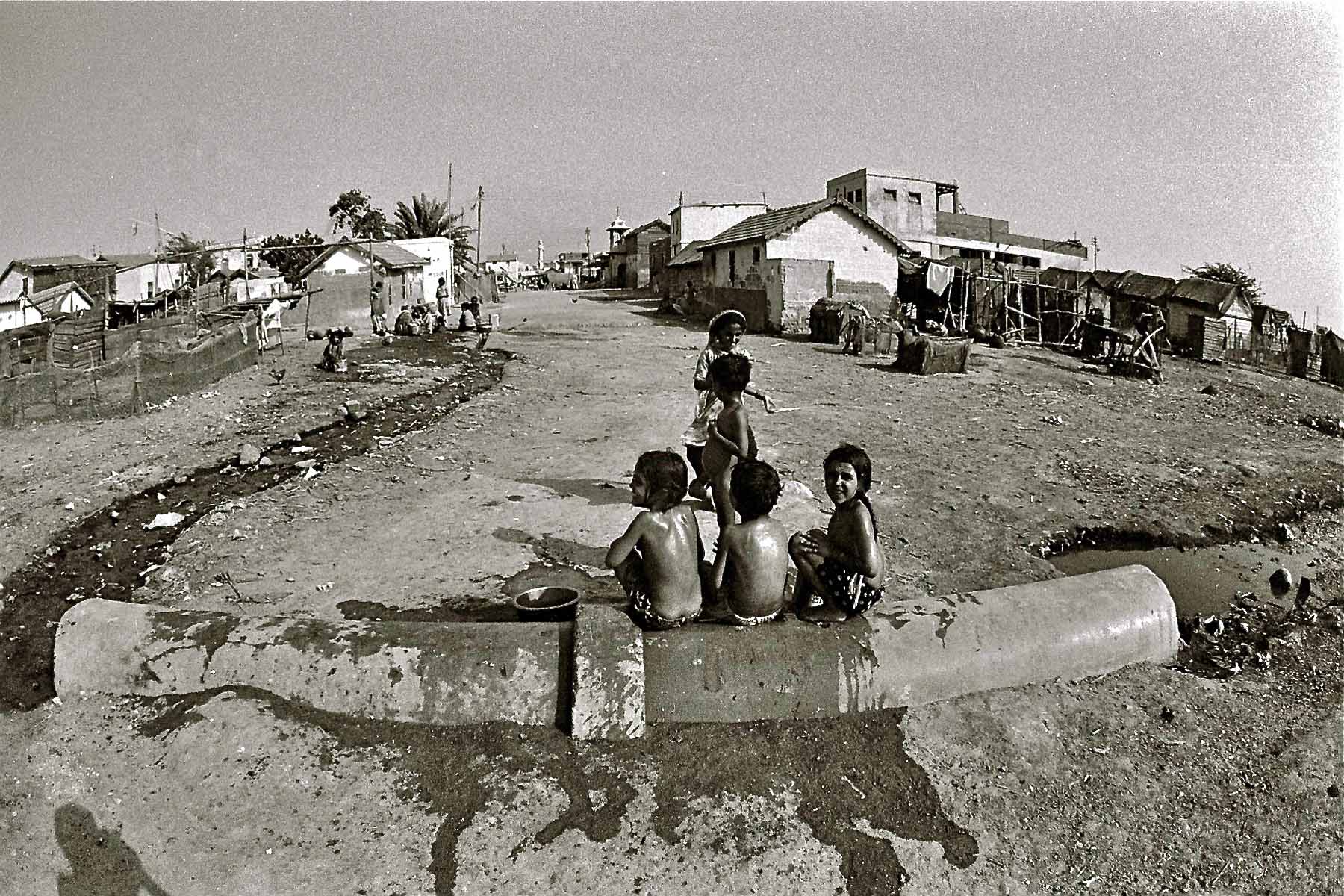

Our report said that ‘the urban discontent in Pakistan, witnessed in the form of agitation and uprising in the closing months of 1968 and early 1969, has brought into sharp focus the underlying causes of civil unrest and strife that are now threatening the very fabric of our society. Whatever may be the nature and form of the protest, and whatever slogans may be chosen to express it, there is no denying the fundamental truth: that the underlying basic causes are the miserable social and economic conditions of the toiling masses.

‘After food, the most demanding and pressing need is that of shelter. And it is shelter that the Pakistani worker is completely denied. It is ironical that in the closing years of the decade, when industrial production should be making unprecedented gains, the worker, who has toiled to make the schemes of industrial expansion a much talked of success, should be living in an unimaginably wretched, filthy and foul environment; that he should be living in overcrowded ghettoes with little protection against the natural elements of heat, cold, rain and sun; that he should be an open prey to all kinds of pathogenic bacteria, causing unending ill health and disease; that he should be living in an environment totally devoid of any social, recreational or cultural facilities.

‘Words cannot describe, nor can any photographs portray the miserable plight of the Pakistani worker’s living conditions. They must be seen to be believed. Under the circumstances, it is only natural that all those who hold the national interest close to their hearts, and who wish to see the spectre of revolutionary change melt away from the national horizon, would like to ameliorate the living conditions of the industrial worker; they would like to see as many wholesome communities as possible come into existence to reduce the misery of the working class.

‘One does not need a profound study or an elaborate survey, to arrive at the conclusion that workers’ housing is the most pressing problem today. So colossal is the need and so meagre are the resources, that the only thing, which has relevance, is the beginning of the construction projects. There is no time for delay in refinements and sophistications. A beginning has to be made immediately.’

However, the third member of the trio, the army, was not in the least concerned with what happened to the civilians, as was clear from their retaining the defence, interior and foreign affairs ministries and distributing the rest between the air marshal and the admiral. This has been the tragedy of the country, that sooner or later all army governments have become occupied with the politics of retaining power, instead of doing the cleaning up operation and handing over power to elected government chosen through a fair and impartial election. General Yahya Khan, therefore, soon brought civilians into the cabinet who could help him in negotiation with the politicians, and sent the air marshal and the admiral off as governors of West and East Pakistan.

With the air marshal and his whizz-kids in power in West Pakistan, Yasmeen Lari was able to thwart the resistance of the bureaucracy in the Sindh Government, and orders were passed to settle slum dwellers where they squatted by providing them with the required infrastructure under her new design ideas.

Her position was further strengthened when under the onslaught of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in West Pakistan and Sheikh Mujibur Rehman in East Pakistan, the army regime with its conservative bureaucracy was overthrown, and fresh ideas found a place. President Bhutto invited her to Murree Presidency to explain her ideas on architecture and town planning for the poor. Mr. Bhutto was at his charming best, standing at the door to receive her and invited his wife Nusrat to meet Yasmeen and have tea with them, besides coming out to see her off to the car.

Dr. Mubashir Hasan, the Finance Minister, came to our house on an Eid holiday and said that Mr. Bhutto wanted her to be czar of architecture, as the government was setting up an architectural consultancy (PEPAC) which would do all the government work and she would head it. But Yasmeen preferred her independence and refused. Mubashir was visibly upset and said, “If you refuse, you will never get another project in the country.” “That is fine,” she said, “I have another option – I will be a housewife.”

However, she was asked by President Bhutto to execute the Angori Bagh Project in Lahore, and the Lines Area project in Karachi as models of what could be done in low-income areas. She insisted that people should be allowed to construct houses instead of flats since they needed to keep birds and animals to augment their income and food intake. Sure enough, as she invited people livimg across the road from the Shalimar Gardens to discuss her design of three-storey, high-density, low-rise walkups with them, the chant went up from women, ‘where will our chickens go’. They were satisfied when she pointed out her design of open-to-sky terraces at each level and said, “This is where the chickens will roam, vegetables will grow and toddlers will play under your watchful eyes.”

Her work for low-income groups became the subject of study at the Aga Khan Programme on Architecture at MIT, and she was invited to lecture there as Guest Faculty Member, MIT-Harvard Seminar, Cambridge, USA, 1981. She in turn invited the faculty of architecture and town planning of these universities to hold short courses on the subject for professionals in Pakistan, to help architects and planners to update their knowledge of the subject. They agreed, and they sent their faculty members to hold classes for professionals working in Pakistan, arranged by her in Karachi.

She was the only architect from Pakistan selected for mention and to have a chapter devoted to her life and work in the book, ‘Architects of the Third World’ (in German) by Professor Udo Kulturmann, 1980. And Asiaweek of Hong Kong named her one of the seven visionary architects of Asia in its issue of 3rd September 1982.

She was also invited by the Aga Khan to Aiglemont, to his home in Paris, when the first experts’ group was chalking out a programme for an award of architecture for the Muslim world. She in turn hosted a dinner for the Aga Khan and his wife in Karachi, when on her suggestion the first Aga Khan Award for Architecture was held in the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore. However, her relationship with Aga Khan group did not last, because as the famous Harvard art historian Oleg Grabar said to her, ‘You are too outspoken. They are afraid that you might rock the boat’. It finally ended when the Aga Khan invited her to Switzerland to offer her the job, but she told him that she could not give up her work in Pakistan, and took the first flight back to Pakistan.