Quaid was Imperious

The Quaid-i-Azam at the time of partition wanted Nawab Iftikhar Husain Mamdot (1905-1969), who had become President of the Punjab Muslim League on the death of his father, to be the Chief Minister of Punjab instead of Oxford educated Malik Sir Feroze Khan Noon (1893-1970), who was High Commissioner of India to the United Kingdom from 1936 to 1941 and Indian member of the Viceroy’s Council from 1941 to 1943. The Quaid sent Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman to ensure that the Punjab Muslim League Assemby party did not elect Noon.

The same was the case in Bengal, where the Quaid-i-Azam preferred Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin (1894-1964) of the Nawab of Dacca family to Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (1892-1963), who with Abul Hashem was architect of Muslim League victory in election in Bengal. Suhrawardy, who was prime minister of undivided Bengal, was not only replaced by Nazimuddin, but was barred from entering East Pakistan, and a special resolution was passed to annul his membership of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly. Therefore, he came to live and practice at Lahore High Court and joined hands with the opposition in Punjab to merge his Awami League with Jinnah League and called it Jinnah Awami League.

Jinnah had got himself elected as the first president of the sovereign assembly of Pakistan on 11 August 1947. He became the first governor-general, the head of state of the independent and sovereign Pakistan on 15 August 1947. On 19th July 1947, Economist had written that Mr. MA Jinnah’s assumption of the governor-generalship of Pakistan gave promise of being a very thinly veiled dictatorship … for the governor-generalship to be held by an active party politician who has stated that his intention of continuing a political leadership after assuming office was an innovation. One observer wrote, "here indeed is Pakistan's King Emperor, Archbishop of Canterbury, Speaker and Prime Minister concentrated into one formidable Quaid-e-Azam."

On 22 August 1947, just after a week of becoming governor general, Jinnah dissolved the elected government of Dr. Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan. Later on, Abdul Qayyum Khan was put in place by Jinnah in the Pashtun-dominated province despite him being a Kashmiri. On 12 August 1948 the Babrra massacre in Charsadda occurred resulting in the death of 400 people aligned with the Khudai Khidmatgar movement.

The Quaid-i-Azam, who had become the president of the All India Muslim League in 1937, never gave it up, contrary to tradition, till it was divided in two eleven years later in 1948, and he according to his own words suffered his first defeat in the Muslim League when Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman was elected first President of Pakistan Muslim League but the Quaid-i-Azam kept his grip on the government. He nominated Nawabzada as the prime minister, chose the cabinet and presided over its meetings, a practice which British monarchs had not indulged in for two centuries. The cabinet passed a special resolution to allow Jinnah to deal with provincial ministers, and in the case of central ministers, his decision was made final.

After the 1945-46 elections, the Quaid-i-Azam had declared that he had achieved the sort of success which even dictators like Hitler and Mussolini had never hoped for, and did not mind behaving in that manner even to those who were closest to him, beginning with his only child, who married a non-Muslim against his wishes.

Raja Amir Ahmed Khan of Mahmudabad (1914-1973) was treasurer of the All India Muslim League, President of the All India Muslim Student Federation and member of the All-India Muslim League Working Committee. After partition the Quaid-i-Azam did not require the religious card therefore when Raja Sahib said that the constitution of the new state would be based on the holy book, the Quaid-i-Azam insulted him and was so rude to Raja Saheb, who was staying with him, that Raja packed his bags and left, although Raja had to wait for hours at the railway station before he got a train, and lived in India and then Iraq rather than in Pakistan after Independence.

The Quaid-i-Azam appointed Yusuf Haroon (1916-2011) as one of the youngest Muslim League members of the Indian Constituent Assembly, and sent him to Bantwa to persuade the Memon community to transfer their business to Pakistan. Yet he threatened Yusuf Haroon with arrest for disagreeing with him. Both of these blue-eyed boys of the Quaid-i-Azam were like family members to him as their parents were friends of Jinnah. After the death of the Quaid-i-Azam, Liaquat Ali Khan made Yusuf Haroon the youngest Chief Minister of Sindh. Yusuf released the dissenting note of Masud Khadarposh to the Hari Commission, in which Masood had condemned absentee landlordism and recommended confiscation of feudal properties to free the peasants from unbearable oppression. Yusuf Haroon also tabled a bill for land reform, which was not liked by Sindhi politicians. Therefore he was sent to Australia as the High Commissioner of Pakistan, where a well-known American magazine nominated him as one of the ten most handsome diplomats in the world. He was known in intimate circles as Sani, which was short for Yusuf Sani, i.e., the Second Yusuf, a name given to him by Jamal Mian for his good looks.

Raja Saheb came to Pakistan after the death of the two Quaids but did not take part in politics. He lived with his daughter in Karachi for some time and then left to live and work in London. His son Sulaiman (born 1943) arrived in Karachi after completing his studies at Cambridge, to woo a Cambridge friend of ours. He was fascinated by our green and purple mulberry fruit trees and asked me to breed silk worms on them. However, after his mother vetoed his idea of marrying and living in Pakistan he went to India and was elected to the assembly in 1985 and 1989 election.

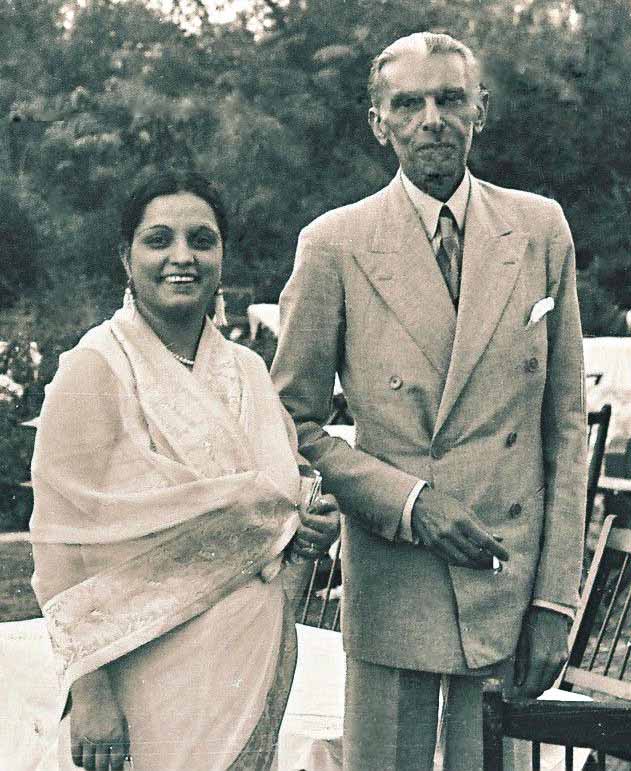

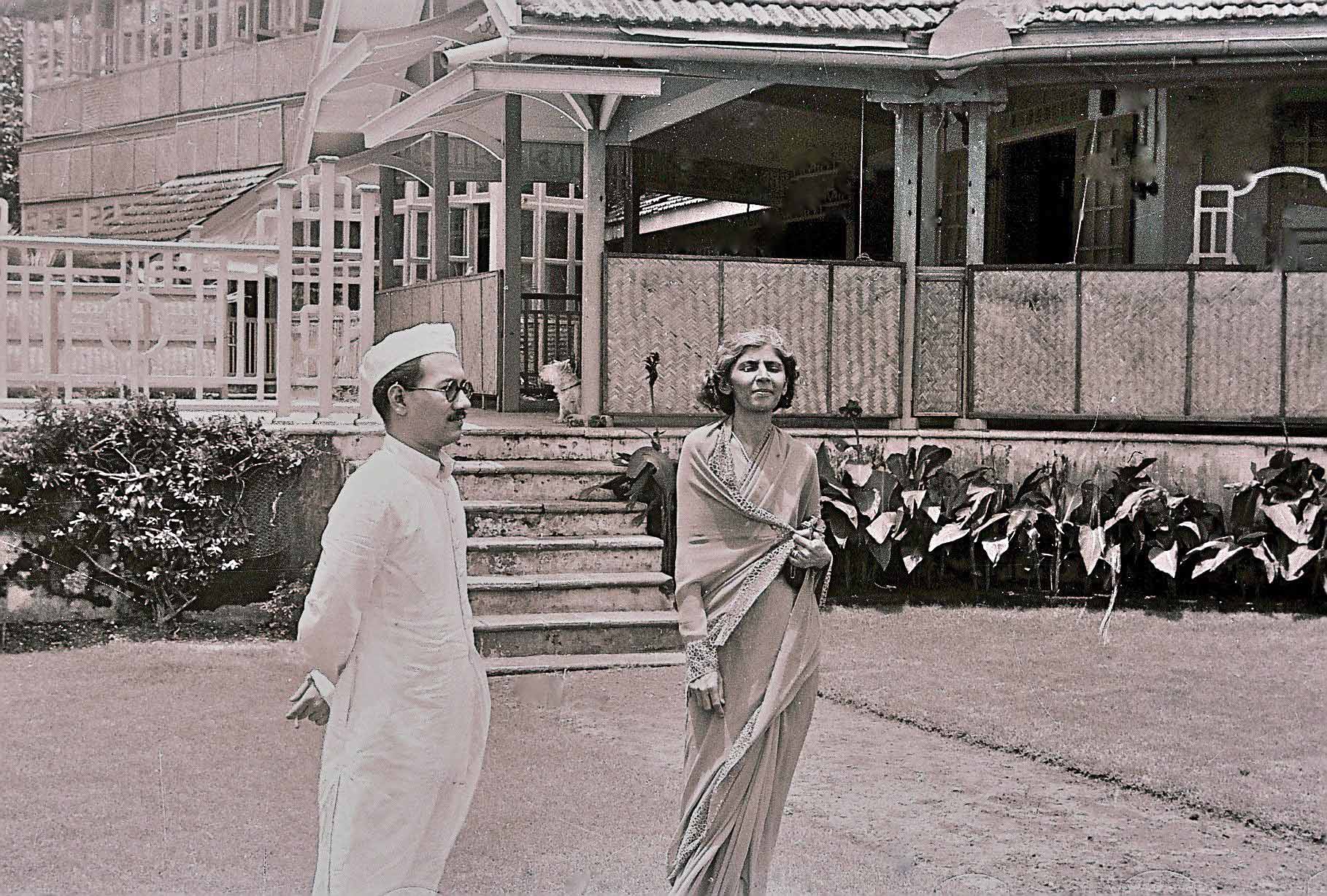

Ashraf Liaquat Ali Khan told me that while going through old family papers his British wife asked him, ‘How come your parents tolerated Jinnah?’. They tolerated him because Liaquat was dependent on him for his position in the Muslim League. Liaquat was born in Karnal in Punjab, therefore he first contested the election of the Punjab Provincial Council but was defeated by a unionist candidate. So he contested the next election for the U.P. Provincial Council from Muzaffarnagar and succeeded from the Rural Muhammadan Constituency in 1926. He was elected Deputy President of the U.P. Legislative Council in 1932 with the support of Nawab Chattari, leader of the National Agriculturist Party. Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan’s second wife was a Christian, Sheila Irene, who had done MA in Economics from Lucknow University and was a lecturer in economics at Indraprashtsa College Delhi. She married him in December 1932 and became Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan. When Liaquat visited London in 1933 with his new bride and called on Jinnah, the university educated liberal couple with same taste in food and drink, a rarity at that time, were an immediate hit with him, though not with his sister. At the twenty-fourth session of the All India Muslim League at Bombay in April 1936 Jinnah proposed the name of Liaquat as General Secretary of the All-India Muslim League. This was contested by a member from Punjab, but Jinnah stopped him from contesting election against Liaquat.

Although Liaquat was nominated by Jinnah as General Secretary of the All India Muslim League and member of the Parliamentary Board, he did not contest the crucial 1937 election on a Muslim League ticket, which was resented by a number of Muslim Leaguers. For example M.A.H. Ispahani wrote to Jinnah on 22 November 1937, ‘… he (Liaquat) is guilty of the same offence as the Nawab of Chattari and Sir Muhammad Yousuf. By his attitude on the eve of last election, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan has forfeited the confidence of the staunch Muslim Leaguers, and I am sure the only one who feels that the proper treatment for this gentleman is either dismissal from the Party or the demanding of an unqualified apology for his past attitude’.

Liaquat’s election as secretary of All India Muslim League again became an issue at the twenty-ninth session of the All India Muslim League in April 1942 in Allahabad. As Liaquat did not think that he could win against my father, he told Jinnah that he would not stand for the secretaryship of the All India Muslim League. Chaudhri Khaliquzzaman told me that Jinnah once again intervened on behalf of Liaquat and told him to stop my father. And the Quaid-i-Azam wrote to Begum Liaquat Ali Khan, saying that if she cared for her husband’s career then she should not skip the evening drink with him.

In America they write about the political mistakes and human frailties of their founding fathers, Washington and Jefferson, including their illegitimate relations with black women without ever thinking that it could in any way affect their contribution to American independence and establishment. Why do we have to believe that if we discuss the political mistakes and human frailties of our founding fathers it will in any way affect their contribution to the creation and establishment of Pakistan? In fact there is a great deal to be learned from their mistakes. It is a pity that those of us who had first hand knowledge of their frailties and blunders have never been allowed to tell the full story.

When I questioned Mirza Abul Hasan Ispahani about the deliberate misstatements in his book on the Quaid-i-Azam, he said, ‘What could I do? After all he was our leader’. Begum Shaista Ikramullah wrote about how she met the Quaid and his sister in Delhi in her book, From Purdah to Parliament (1963), with her uncle, but failed to mention how badly her favourite Suhrawardy, was treated by the two Quaids. When I pointed this out to her she could only say that her husband was in the service of the government of Pakistan. However, over two decades after the death of her husband, and three decades after the death of the two Quaids, she styled herself as Begum Shaista Suhrawardy Ikramullah, and wrote a biography of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (1991), and mentioned the treatment meted out to him without mentioning the role of the two Quaids. Such was the mindset of people who could have told the truth about our freedom movement. There was only Yusuf Haroon who was prepared to say that if he had another life he would support Lari against Jinnah every time because Lari always spoke the truth’, but was told by Jamal Mian (1919-2012) not to speak in public about it. When Jamal Mian came to my house with Begum Ikramullah he gave the same advice to me, although he was full of praise for my father for his guidance to him in the assembly.