Oxford

My father wanted me to be a lawyer and he was opposed to my studying abroad unless I obtained admission to a prestigious university like Oxford or Cambridge. He believed that a lawyer did not have to go abroad to learn the law of his country. In any case, in those days, the State Bank allowed foreign exchange only for very few prestigious universities and courses sanctioned by the Government of Pakistan. Therefore I applied for admission to the Education Attaché in the Pakistan embassy in London, who replied that Oxford and Cambridge had a waiting period of three years. So I began to search for someone who could help me gain admission before that. I came across the name of Sir Isaiah Berlin, who was considered the British political thinker of the twentieth century, for his ‘Two Concepts of Liberty’, as John Stuart Mill was for the nineteenth century for his book, ‘On Liberty’. What was common between Sir Isaiah and me was that I had read and admired Tolstoy, and Sir Isaiah had written a book on Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’ called ‘The Hedgehog and the Fox’. I decided to write to him about it, and I received an invitation from him to come to Oxford. As a precaution I had also applied to Heidelberg University in Germany and took the entrance exam for LSE in London as well, and was accepted at both places. With so many admissions in prestigious academic institutions in Europe, my father could not refuse, and the State Bank of Pakistan also allowed me the foreign exchange required to study in the UK which was sixty pounds per month for Oxbridge and fifty pounds for the rest of universities. I chose Oxford because my cousin Yasmeen, whom I had met in Lahore, was then in London studying architecture, and I was in constant correspondence with her from Karachi. In those days the post was very efficient. You put your aerogramme in the post box in London and the next day it was delivered at your house in Karachi, and vice versa; therefore we wrote to each other every other day. There was no need to resort to couriers, which in those days in any case did not exist, and there was no need for them to exist, as the postal system of those days was more efficient than any courier service of today.

On the way to Oxford I spent a day in London walking around town, and while strolling round Piccadilly Circus I bumped into a Pakistani student at Oxford whom I had met in an inter-collegiate debate. He invited me to dinner at his college at Oxford. It is most unfortunate that we could not remain friends, because he was inclined to woo ladies who were also known to me, and trusted me to be truthful with them. Therefore when they asked my opinion of him, I gave it frankly to them as their friend, saying that, ‘He is wedded to success and would do anything to succeed and is therefore bound to succeed and nothing else is of interest to him, except what would help him in furthering his ambition’. When the first three ladies that he wooed did not marry him he blamed me, although I never opposed their doing so. In fact, I thought that my assessment of him would make him more attractive to some. This was the case with the lady who married him, despite the fact that her uncle and her poet friend tried to dissuade her from doing so, because they believed that she was a sensitive and artistic soul who would not get along with him. Unfortunately, this happened at our open house, which again made him think that it was my doing although I was incapable of making the scathing comments that they made about him, which were reported to him by his intending wife. But as daughter of a civil servant she was made of sterner stuff, and listened to my advice, and opted to enjoy the life of success and high office that I predicted for him, despite the fact that Ardeshir Cowasjee described him as the biggest Lota in Pakistan politics for becoming part of a parallel PPP created by Niazi and Jatoi, as soon as Bhutto was hanged, to curry favour with General Zia ul Haq, and then attaching himself to Benazir Bhutto when she arrived in Lahore, after years of exile, to great crowds welcoming her.

When I arrived the next day at Oxford Railway Station, Sir Isaiah’s car was waiting for me, and took me to his house where he was playing croquet with Lord Rothschild, one of the richest men of Europe at that time. I was invited to join them in the game, and at tea Sir Isaiah asked me what I would like to do. I said that as I had done B.A. (Hons) from Karachi University, therefore I should do a postgraduate degree. Sir Isaiah laughed and said that, ‘This is what Americans do, but we at Oxford merely do B.A. and learn to think’. He advised me to study what he had done at Oxford i.e., Modern Greats, which comprised Philosophy, Politics and Economics. I agreed, and he phoned Sir Alan Bullock, author of ‘Hitler - A Study in Tyranny’, and the founding master of St. Catherine’s College, who asked me to come over the next day. In those days, once you obtained admission at an Oxford college you put on a gown and could attend any lecture, so I attended all kinds of lectures on all kinds of subjects except my own. I skipped them only when someone from the subcontinent came and asked me to let him attend a lecture by some important poet, artist or thinker. I gave my gown to them, as that was the only requirement to attend any Oxford lecture in those days. There was no record of attendance. The only other requirements were the dinner at the college, and production and defence of essays on subjects given by tutors. My philosophy tutor was a Greek who was always immaculately dressed, drove a beautiful Bentley and was a friend of novelist Iris Murdoch, who had dedicated one of her novels to him. He was very careful about his health, thus one way of getting away from him was to sneeze or wipe your nose as you entered his room, and he would immediately start spraying the room and ask you to leave. This was a device which we used when we were not satisfied with the essay we had written for him. My economics tutor was an Australian with an Irish sounding name. Only my politics tutor was an Englishman.

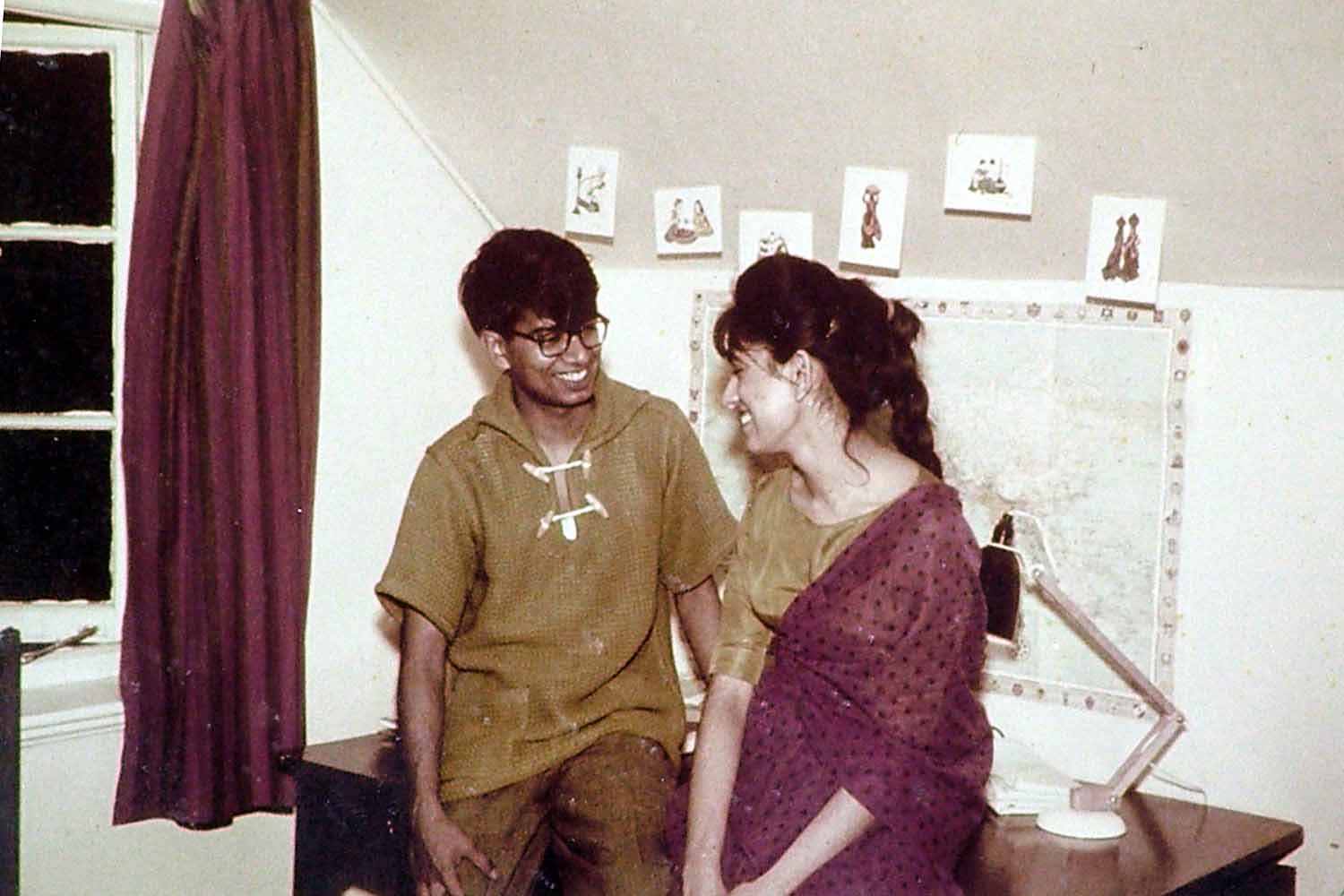

At Oxford I stayed at 5 Canterbury Road in the ground floor room, which was the largest room in the house. For that reason it was most expensive to keep warm, and hence the most easily available, but because of space it also became the focal point for the meeting of friends. On Saturday mornings I went for 10 am coffee at Cadena Café, which had been made famous by the author of Alice in Wonderland who saw a little girl peeping through its glass window. Here I was joined by others, and from there we moved to Mrs. Palmer where I bought all the ingredients for a curry and rice lunch with paper cups and plates. Together we cooked for the twenty or more who gathered by 2 p.m. Sometimes a Bengali lady, a lecturer at Calcutta University, also prepared roshogolla for those who stayed till evening discussing some hot topic of the day.

Apart from university students, Oxford used to be full of young boys and girls who would come from all over Europe to learn English as students in language schools or as au paires attached to English families. It also attracted a number of oil-rich Iranians in their flashy cars, who played havoc with these girls, with their money and lies. My room was the largest dance floor available to them. I remember that one sweet Indian girl from East Africa, who later made a name for herself as a writer, became pregnant by an Iranian boy who then vanished. So I had to look after her till she got over her embarrassment with doctors and health workers over being pregnant without a boyfriend, and gave the child away in adoption. This was much before the oil-rich Arabs invaded Britain.

I was keen to get married to my cousin but our family wanted us to complete our studies first. Therefore, I went to Gretna Green in Scotland where girls not yet legally adults were allowed to marry without permission from their guardians, and we announced to our parents that we were getting married. At this they relented and arranged our marriage in Karachi, and when Yasmeen completed her intermediate in architecture from London I arranged for her to move to Oxford to complete her studies there.

After our marriage we moved to a flat at 176 Banbury Road, Oxford, where I continued the habit of hosting an open house on Sundays. To accommodate so many people we cleared our flat of all furniture, to the delight of my landlady, and invited everyone to sit on the floor. My neighbour anthropologist Senayake Bandaranayake (later Professor and High Commissioner of Sri Lanka to India and France) loved to sit at the feet of Sir Isaiah Berlin, and used to say he felt that he was in the presence of a guru. Actually Sir Isaiah had a beautiful way of talking, as he never contradicted anyone but merely asked, ‘Would you like to consider or may I suggest?’

After Kennedy took office as president he sent a plane to fetch Sir Isaiah Berlin for the weekend to stay with him at the White House so that he could talk to him during lunch and dinner.

Sir Isaiah brought to our lunch Richard Neustadt whom President Kennedy had asked after election as President to do a paper for him on presidential power which was later printed as a book. Neustadt quoted President Truman as saying that General Eisenhower after election would sit here as president and say do this and do that, but nothing would happen.

My landlady was a kind woman. She did not mind my giving refuge to my friends who were looking for a place to hide for one reason or another. Here I can take the name of Farid Riaz because he loves to tell his story to everyone. One day he came to us saying that his landlady’s lover was after him, so he needed to hide somewhere, and stayed with us. Another friend was Adrian Akbar Husain, who had come from Moscow where his father was ambassador. He was brimming with Russian literature and tales of the British MI5. He won the Guinness poetry prize, and is the finest living Pakistani poet writing in English. My father also came to stay with me and stayed in the room made available by Senayke Bandaranayake who was off on a long holiday. The restriction on the amount of foreign exchange that the State Bank allowed, meant that a number of people arranged for their contacts to leave foreign exchange with me, which they later collected when they visited Oxford. One such person was Chief Justice Inamullah who was a friend from Allahabad.

Further, as head of various Oxford societies I invited important speakers to dinner. For example, I was President of Oxford Majlis when the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference took place. I invited President Ayub, Prime Minister Pandit Nehru and Mrs. Bandaranaike. I received a letter of refusal from President Ayub, signed by Altaf Gohar. I was not surprised because my father had made a scathing criticism of martial law as the President of the Bar in a speech at its annual dinner, which was highlighted by the western press and ‘The Time’ magazine, headlined it as the ‘First Voice of Freedom’. Mrs. Bandaranaike could only make a brief visit, and I showed her round Oxford Union, of which her assassinated husband, prime minister Bandernayke had once been a member.

Pandit Nehru accepted the invitation. When I received him at the railway station he was depressed, as his long-term colleague and deputy prime minister, Pandit Pant, had died. To cheer him up his sister Ms. Vijay Lakhshmi Pandit asked him to congratulate me on my engagement. The Nehrus were not only our neighbours in Allahabad, Ms. Pandit had entered the U.P. Assembly at the same time as my father had. She was now the Indian High Commissioner in London and on her way to London was told about my engagement by my father. In those days one did not get any news from home unless someone decided to write a letter, as the phone connection with Pakistan took many days to arrange and was often bad. Panditji perked up by the time we reached the Oxford Union building because he challenged me to a race up the stairs. After the reception by the Oxford Majlis, and his speech at Oxford Union, Nehru continued talking to us till early morning in an introspective mood, saying that as a government functionary he had to take stands which were contrary to his conscience. He gave the example of Mahatma Gandhi who according to him was free to speak the truth according to his belief.

When ‘A Passage to India’ had its premier at Oxford Playhouse, I was President of the Pakistan Society, and invited Zia Mohyeddin to my digs, where he spoke to us lying down on the sofa. The most formal society that I was president of was one dedicated to international affairs called the Bryce Club named after Lord Bryce, the secretary-general of the League of Nations, which was based at Nuffield College and was popular with rich South and North Americans. We gathered in the reception area to receive the chief guest with beer, followed by his speech in the hall, dinner in the dining room, and drinks in the study, where warm port in a silver trophy with a large silver spoon was available, and ended the evening with coffee in the library. Nuffield was a special postgraduate college founded in 1937 by a donation from Lord Nuffield, owner of Morris Motors for the study of social sciences. Here admission could be for a specific term, which was availed by politicians and administrators from various countries, to acquaint themselves with the latest developments, and innovations in government and society. I remember having interesting discussions with a number of American congressmen and Israeli politicians who had the habit of taking time off from their work and coming to Oxford, to get an understanding of the latest developments in the world of art and science. An interesting person was Yigal Allon who was then labour minister and a former general in the Israeli army. Another was the first Greek-American congressman, John Brademas, who later served as the majority whip of the US House of Representatives.

One of the most interesting institutions of Oxford is All Souls College, which was founded by King Henry VI in 1438. He also founded Eton and Kings College. All Souls College has no students. It has only professors and fellows, a few of whom are selected each year to become its members. It was a treat to be invited there by Sir Isaiah for dinner, as one met some of the greatest minds.

As President of Oxford Majlis, I invited former labour prime minister Earl Attlee to dinner. He insisted that he had no plans for or against Pakistan, but was merely determined that Britain should leave India as soon as possible. The future Indian Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, lived near us with his wife and daughter. He had studied economics at Cambridge and had come to Oxford to do a PhD. He complained that if he looked at a page he could not forget it. Manmohan had a photographic memory. Therefore the only time he came to Karachi, which was to attend the Conference of State Banks of SARC countries as head of the Reserve Bank of India, his memory did not fail him. He surprised me by arriving at my house without notice so that I could not inform my wife of his visit. Manmohan’s daughter mentions it in her book on her parents and states how at Oxford her father dropped in at our house, and engrossed in discussion, lost track of time completely while her mother waited anxiously at home.

Another Indian from Oxford days who visited me was Girish Karnard who has become famous in India as a writer, director and actor. He came with his wife and three other South Indian writers who were keen to see the Indus River because in the morning when they washed they took the name of all the sacred rivers which they had seen, but for the Indus. Therefore I took them to see the river Indus, and on the way showed them Makli necropolis and Thatta mosque. Another Indian friend at Oxford was Prem Shankar Jha who was the son of ICS Jha who was batch mate of my uncle.

Some of the Pakistanis at Oxford whom I got to know were bureaucrats Muzaffer Mahmood Qureshi and Saidullah Khan Dehlavi, businessmen Zia Khaleeli and Raza Kuli Khattak. Also intellectuals like Badruddin Umar who was the son of Abul Hashim, General Secretary of Bengal Provincial Muslim League, and the main proponent of one Bengal at the time of partition. Badruddin wrote nearly a hundred articles and books, and made a name for himself as the Marxist-Leninist historian of East Pakistan. He left his radio for me saying that I should listen to English plays, which I also recorded on my Grunding tape recorder.

There was a Pakistani who came from London for the day to acquire knowledge of Oxford colleges, their professors and the subjects they taught. He had no qualifications except that he was employed as a night watchman at the Pakistan Embassy, and spent all night watching BBC television to acquire the dress, manners and accent of the British aristocracy. He started wearing a striped suit with brolly and bowler hat. He became a member of the Tory party, got into diplomatic circles and married the Burmese ambassador’s daughter. He came to Pakistan as a highly educated gentleman from Oxford with appropriate accent and manners, and was given a job in a reputable company. I was oblivious of his exploits till one day Ghazi Salahuddin told me that he had been a clerk in an income tax office till he managed to bamboozle a client into sending him to the UK. It was a pity because he had a sweet wife and daughter who left him when he was exposed.

Another interesting figure I met was the famous cricketer A.H. Kardar, who was an Oxford Cricket Blue and had been sent by the Saigol family to arrange admission for their children in Oxford. He was successful, because soon the Saigol boys and girls came with their mother. Javed and Shahida Saigol stayed on at Oxford and came for tea at our digs with their mother. I also became acquainted with Farooq Leghari, who after a career in civil service joined politics to become President of Pakistan, and Muin Afzal who joined the civil service and became Secretary General of Finance and Economic Affairs.

And I met again a Sindhi friend from SM College days named Namoos. He was a philosophy scholar in the habit of making short, clipped, logical statements. Namoos and I had intense discussions on philosophy and religion with his friend Talal Asad who was an anthropology student. Talal was the son of Muhammad Asad, the famous Austrian Jew who converted to Islam and was the author of Road to Mecca and translator of the Holy Quran. They had both come from a Scottish university to Oxford for a year on a research scholarship. Talal went away to Sudan to teach anthropology at Khartum University and Namoos went back to his Scottish University to teach philosophy. After that I lost track of them till one day Namoos came to see me in Karachi with his Austrian wife. As usual he was reserved about himself but his wife told me that he had given up academia and opened a shop, which they ran together in Scotland. It was a surprise, because I always thought that Namoos would one day make a name for himself as a philosopher. They seemed to be happy but a few weeks later I heard that his wife had left him and Namoos had committed suicide.