ICS

In Lahore we stayed with my father’s younger brother, Zafarul Ahsan, I.C.S., at 88 Jail Road. According to the private secretary of the last two viceroys, Sir GEB Abell, the British Government had given two gifts to Punjab, one being my father-in-law and uncle, Mr. Zafarul Ahsan, who was Deputy Commissioner of Jhelum. From there he was brought to Lahore on 11th August 1947 as Additional Deputy Commissioner, and was made Deputy Commissioner of Lahore on Independence Day 14 August 1947, with additional charge of refugee camps and refugee rehabilitation at a time when Lahore was, according to some, ‘the city of the dead and a picture of hell’.

In Punjab, the Unionist party had cut across class and community interest, and brought about consensual approach to politics by building bridges across communal divides and between rural and urban communities and had brought together feuding Congress and Akali parties. They were helped in this by Muslim, Hindu and Sikh in same family who had a common Punjabi language and shrines. Sufism had reached out far beyond existence of the Muslim community with such sufi poets as Sultan Bahu and Bullhe Shah. Baba Farids verses were incorporated in Sikh holy book the Granth and Mela Chiraghan celeberated devotion of Muslim Lal Husain for Brahmin boy Madhu.

However, another trend was coming to fore as a reaction against modernizing impulse of colonial government which promoted loyalty to raj and threatened religious outlook.

The Urban Ulema and Chishti revivalist pirs sought to purge sufism of un Islamic practices.

Sikh Tat Khalsa (True Khalsa) founded in Lahore in 1879 sought to purge Sikh gurdwaras.

Arya Samaj (Society of Nobles) was founded by Hindu sannyasi (ascetic) Dayanand Sarasvati in 1875 at Bombay to re-establish Vedas among Hindus.

They all believed in a golden age when there faith was pure and unsullied to which they harked back as only truth.

Urban Punjabis were independent of colonial administration. Muslim Anjumans and Hindu and Sikh Sabhas represented new kind of consciousness which undercut shared cultural values and practices of rural population.

This was furthered by the press in cities. Muslim and Hindu elites denied that Punjabi was there mother tongue. They portrayed Punjabi as sikh language. Hindu promoted Hindi in Devanagri script and Muslim Urdu in Arabic script.

The March 1946 election was fought by Muslim League against Unionists as traitors of Islam, and referendum on Pakistan with cry of Islam in danger. It ended twenty year dominance of unionist party in Punjab. In a house of 175, AIML emerged as the largest party with 73 seats, followed by Indian National Congress 51, Shiromani Akali Dal 22, Unionist Party 20, Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam 2 and Independents 7. As AIML parleys with Akalis broke down, the Unionist government of Tiwana was sworn at the head of a coalition with Akali and Congress on 11 March 1946.

Muslim League began agitation against Unionist coalition government on 24 January 1947. It led to resignation of unionist government of Tiwana on the 2nd March 1947 and resulted in rioting in Lahore on morning of 4 march which claimed five lives. In the afternoon there was arson attack on Hindu business in the walled city that continued on 5th and 6th march. Shah Almi which was the Hindu commercial and residential area in the walled city of Lahore, was destroyed in a great fire.

There was simultaneously rioting in Amritsar on 5th march in which about four thousand Muslim shops and businesses were destroyed and eight thousand houses were destroyed.

Communal violence spread from cities to villages as whole villages in Jhelum, Attock and Rawalpindi were put to sword in which seven to eight thousand were killed. And about forty thousand Sikhs took refuge in camps

Muslim ex-servicemen stock piled weapons from frontier while Sikhs were armed by princely states. It ended any hope of united Punjab. Punjabis ceased to be Punjabis and became Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs.

The estimated loss of life during the partition of India is two to twenty lac. Besides it involved largest displacement of people in twentieth century variously estimated between thirteen to eighteen million people who were forced to cross the international border in search of safe havens. Out of which there were ten million Punjabis who were displaced by partition. In Lahore alone there were a million refugees of which two fifth were housed in camps.

Quaid-i-Azam arrived in Lahore by air on Thursday 28th August 1947. He conferred with West Punjab ministers, and later Refugee Minister Ghazanfar, Governor Mudie, and GOC Rees of Punjab Boundry Force.

The Indian Governor-General Lord Mountbatten arrived by air on Friday 29 August 1947 morning and was taken to Government House. Indian Prime Minister Nehru, Defence Minister Baldev Singh went with Revenue minister Shaukat Hayat to his residence at 9 Club Road. The Chief Minister Mamdot received Governor Trivedi of East Punjab and his two ministers Bhargava and Swaran Singh at the airport. Later Liaquat and Nishtar also arrived.

The Joint Defence Council met at 11 am at Government House on Friday 29 August 1947. The Governor General and Prime Minister of India and Pakistan, Governor of East and West Punjab, Supreme Commander Auchenleck, Commander-in-Chief of Pakistan and Indian army Messervy and Lockhart, Maj. General Rees commander of the Punjab Boundary Force, were present. As 70% of attacks on rail took place outside the Punjab Boundary Force area. PBF was abolished from Midnight of 31 August 1st September and direct control of areas was given to two dominions.

A four-day programme of tour of riot-affected area by ministers of both countries was arranged. Nehru and Liaquat left for a tour of Amritsar, Gurdaspur and Batla on Saturday 30th morning. Sardar Baldev Singh and Sardar Abdul Nishtar left for Gujranwala and Sialkot.

The Joint Defence Council of India and Pakistan, declared that illegal seizure of property would not be recognised, and that each government would appoint a custodian of refugee property to stop such illegal seizure, while the evacuee property was to be distributed among the refugees of the two countries, after exchange of information between the two governments.

Zafarul Ahsan had to face a tremendous amount of resentment from locals, who believed that the property left by Sikhs and Hindus belonged to them. And therefore they had looted and occupied it. He had to show great tact to get them out of the illegally occupied properties and settle refugees in them. It split the ruling party and led to agitation against Urdu speaking officers, and the British governor, Sir Francis Mudie, was accused of replacing Punjabi speaking officers with Urdu speakers.

‘Way nakami mutay karavan jata raha

karavan kay dil say ihsas ziyan jata raha’

Hafizur Rahman wrote in Dawn, ‘Zafrul Ahsan was an ICS from eastern UP, but not one of the thousands that he helped as deputy commissioner of Lahore immediately after the horrors of partition, was Urdu-speaking; they were all refugees from East Punjab. (Isn’t it strange how the meaning of “refugee” has changed over the years?) It was a crowd that blamed Pakistan for their misery, and saw nothing grand about the new country. Zafrul Ahsan ran about like a mad person to provide them shelter in a house or a vocation in a shop. Only some of them were grateful because they thought this was their right, others even abused him when they couldn’t get what they thought they deserved. He showed exemplary patience in carrying out his duty and sympathy for the sufferers. It was love for humanity all the way.’

Zafarul Ahsan had received a further additional charge as Chairman of the Lahore Improvement Trust on 1st September 1947, to rebuild Lahore. He rebuilt the burnt out Shah Almi in the old town by widening the road and developed new areas like Gulberg and Samanabad, to cater for the influx of population. He was the builder of post-independence Lahore.

Apart from the Lahore Improvement Trust, Zafarul Ahsan was also given the charge of the Thal Development Authority on 26 May 1949, comprising the districts of Mianwali, Bhakkar, Muzaffargarh, Layyah and Khushab, to create new settlements. He created new cities called Jauharabad, Quaidabad and Liaquatabad by granting land to anyone who was prepared to settle and work there, thus drawing them away from old towns which were being choked by the influx of refugees. He was very strict about it. Anyone who tried to be an absentee landlord and did not pay his dues had his allotment cancelled, which made hi many enemies, including General Ayub Khan, whose allotment was cancelled when he failed to pay his dues despite notices. According to H. N. Akhtar, Zafarul Ahsan was the first to build highways in Pakistan in a straight line from one point to another. Zafarul Ahsan spent most of his time driving between Lahore and the desert of Thal. I sometimes accompanied him as I had some friends of Pakistani origin from Kenya who had been settled there. I also got hold of his Punjab Public Library card and went through its great collection of Urdu literature.

Hafizur Rahman wrote in Dawn, ‘The Thal was a desert in the western part of the province and the Punjab government was determined to make it suitable for agriculture and to colonize it. He achieved miracles there, just because he came to know every inch of the desert. …. The hallmark of Zafrul Ahsan’s three years in Thal was pure initiative rarely found in government officers. Once a pressman asked him how he was able to satisfy the Accountant General who did not tolerate unorthodox ways of spending public money. I shall never forget his explanation. He said, “Whenever his office asks me to quote the rule under which I have incurred a certain expenditure, I write back asking them to quote the rule that prevents me from doing so. I hardly ever get a reply. I’m afraid the AG is very annoyed with me.”

A history of PIA has the following to say, ‘In 1956, orders were placed for two Super Constellations and five Viscounts which were to be delivered in 1959. At this juncture, PIA possessed a small fleet, which comprised of Convairs, Viscounts, Super Constellations and DC-3s. It was the first Managing Director of PIA, Mr. Zafar-ul-Ahsan, who in his 4-year tenure got the ball truly rolling and set the shape of things to come. The PIA Head Office building at Karachi Airport, which houses all the major departments of the airline, was the brainchild of Mr. Zafar-ul-Ahsan. In fact, on his departure from the airline, the employees presented him with a silver replica of the building with the caption, "The House You Built".

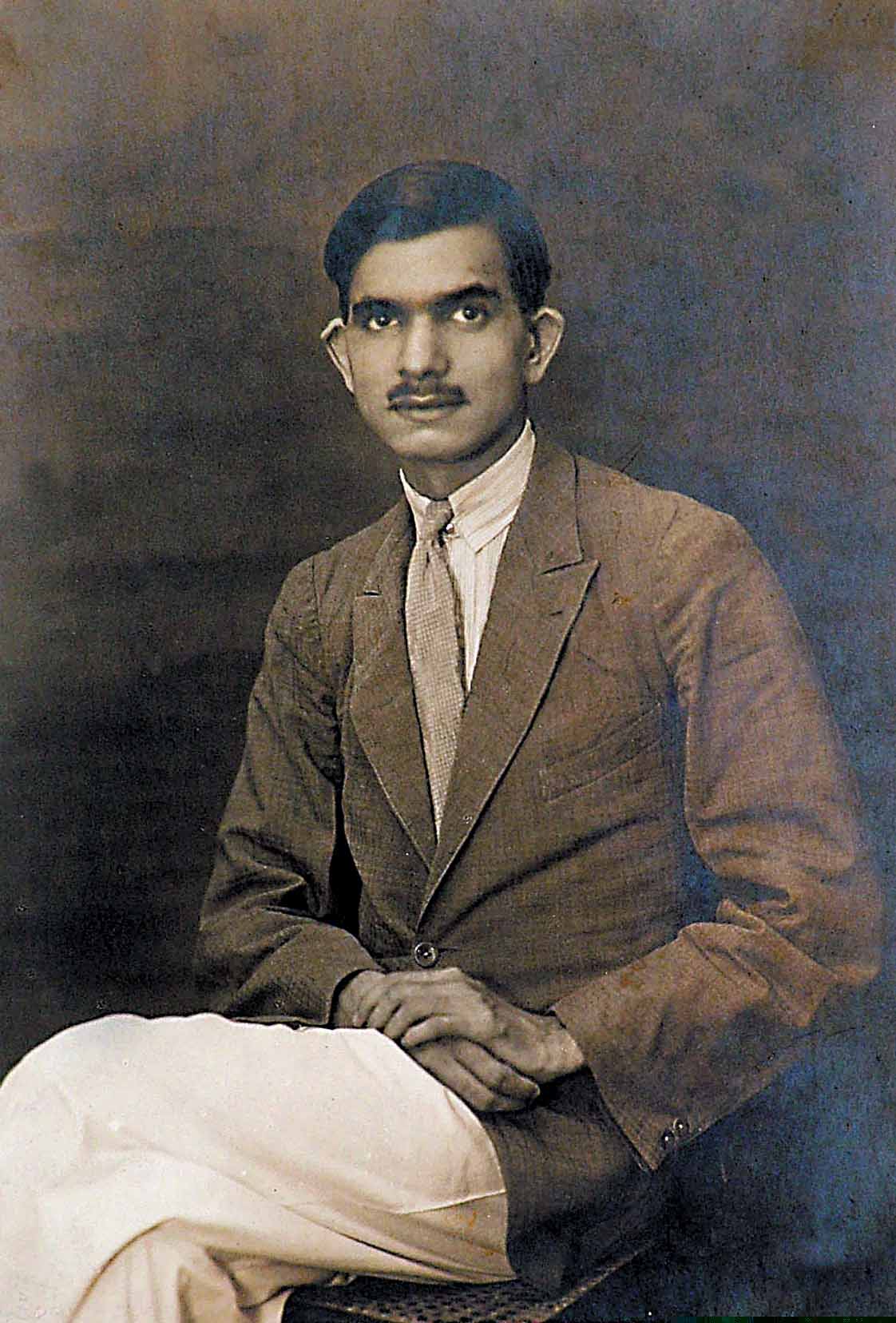

Zafarul Ahsan was the only Muslim to be declared successful, along with three Hindus, in the 1934 ICS examination held in Delhi. The British government was not happy at the proportion of Muslims among the ICS officers; therefore they decided to nominate Muslims from among those who had appeared in the examination. This resulted in an immense amount of lobbying.

The Imam of London Mosque pressed the claim of Mr. Nyazee on Mr. R. A. Butler, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for India, as the only Ahmadi candidate for the Indian Civil Service. Mr. Butler passed on the Imam’s letter with the note that he could not support Mr. Nyazee, and was simply passing on his letter for what it was worth. The Imam wrote, ‘Mr. Nyazee stood 8th in order of merit at Delhi Centre in January 1933 and first in Punjab, and then hastened to England to try his last chance. He stood 85th in order of merit after barely two months of preparation ... Nyazee Afghans of Mianwali have always distinguished themselves for loyalty and particularly in military service during and since the Mutiny.’

Mr. Zafarullah Khan, later Foreign Minister of Pakistan, wished to see Mr. Arshad Hussain, who was a nephew of Sir Fazl-i-Husain, nominated to the Indian Civil Service. He had competed in the Delhi examination in January 1933, and was placed 9th out of 210 candidates, while in the London examination in August 1933 he was 58th out of 277 candidates. Mr. Zafarullah Khan wrote from ‘Dil Afroze’, Model Town, Lahore on 26 April 1934 to Sir Findlater Steward, ‘You will recall that last year I mentioned two names to you in connection with these nominations, those of Mian Arshad Husain (nephew of the Honble Mian Sir Fazl-i-Husain) and of Mr. A.K. Nyazee.’

Sir Mirza M. Ismail wrote on 19 May 1934 from Carlton House, Bangalore, to ‘My dear Sir Findlater Stewart’, recommending his cousin and ward Aga Hilaly for nomination to the ICS. Mr. Hilaly was rejected on medical grounds, as he did not come up to the I.C.S standard on weight and measurements. Sir Mirza M. Ismail wrote to Sir Findlater Stewart that ‘the medical board had been too strict. It had not found any organic defect, and weight and measurement can be changed with exercise and tonic.’ The secretary of S & G asked, ‘I would be grateful if you would say what reply can be given to Sir Mirza M. Ismail. I attach some correspondence which Sir Findlater Stewart recently had with Mr. Zafarullah Khan on the same subject of nomination for the Indian Civil Service.’ ‘One of the rules under which nominations are made prescribes that if any candidate seeks to enlist political influence in support of his claims, it will count against him. Nevertheless the practice of Indian politicians supporting their protégées for nomination seems to me to be growing. I suggest a reply to Sir Mirza M. Ismail which is as cold in its terms as is politically wise.’

Mr. Shafiq Jalil Asghar pleaded for nomination to the Indian Civil Service. He wrote on 18 October 1934 that he had appeared in the Delhi examination in January 1933, and in the London examination in July/August 1933. He added that he had no further chance to appear, and that his father, Shaikh Asghar Ali, had served in Punjab for 35 years and had been granted the title of CBE.

The Home Department of the Government of India telegraphed from Simla on 2 June 1934 to the Secretary of State, saying that the Public Service Commission recommended two Muslims for nomination out of the 50 Muslims who had appeared in Delhi examination, one being Musarat Husain Zubairi from the U.P., who had been placed 6th in the examination, and the other being Aga Hilaly from Mysore, who had been placed 9th in the examination. A grateful Sir Mirza M. Ismail sent a few silk handkerchiefs to Sir Findlater Stewart on 28 August 1934. Sir Findlater Stewart acknowledged the gift vide his letter dated 6 October 1934, saying, ‘They are very pleasant gift and it was very good of you to think of sending them.’

A further three Muslims were appointed from among those who had appeared in the open competitive examination held in London for appointment to the Indian Civil Service. One was Shujat Osman Ali who gained 14th position, the second was Shafiq Jalil Asghar who had obtained 86th position and the third was M. S. Sait who had obtained 92nd position in the London examination.

Mr. Zafarul Ahsan, who was at that time an ICS probationer in Oxford, wrote on 22 October 1934 from St John’s College, Oxford, to the Secretary, CSC, in response to his letter dated 15 October 1934 assigning him to Punjab, ‘I was selected by the Government of the U.P. for the U.P. Civil Service in 1932, and served from 7 February 1933 to 16 July 1934 in Aligarh, therefore I should be assigned to the U.P.’ But his request was turned down.

In Lahore, my uncle had a large number of interesting friends who stayed with him in his annexe, especially rebels like M. Masud, I.C.S. (1916-1985), to whom no one was willing to give a posting because of his radical views and conduct. Unlike other I.C.S. officers Masud Sahib was always dressed in a Kurta Shalwar made of coarse khaddar, so he was known as Masud Khadar Posh. He was known in Bombay Presidency as Masud Maharaj, a name given to him by tribal people who loved him for his work among them. He was posted to Sindh just before partition as Collector of Nawabshah and made a member of the Hari Committee. This made him very unpopular among Sindhi politicians as he ‘advocated the liquidation of the zamindar and the creation of peasant proprietorship, in order not only to solve the problem of the hari, but also to help refugee resettlement’. His contention was that the wealth of a nation is its manpower and that Sindh should, therefore, consider itself fortunate to have received a large inflow of refugees. Therefore his note of dissent was not published by the Hari Committee, whose Report on Agricultural Reforms in Sindh published in December 1948 stated that ‘Feudal lords are the best friends of the peasants, who only repay their saviours with ingratitude’. The religious leaders backed the feudals and a pamphlet entitled, Ishtrakiyat Aur Zraati Masawaat, signed by 16 religious leaders, supported absentee landlordism and the findings of the Hari Committee. And Masood Khaddar Posh, the dissident member, was attacked as a socialist and an atheist. Therefore he was first moved to Karachi and then to Punjab, where he again created a problem for the administration by reciting the Azan and then Eid prayers in Punjabi. He was an ardent believer of education in the mother tongue, and wrote a book entitled ‘Mian Mithu’, attacking education in foreign tongues. When Field Martial Ayub Khan contested the election against Miss Fatima Jinnah, he came to me with his English notes against the Indus Basin Water Treaty with India, and asked me to render his ideas in Urdu and distribute them among the Electoral College, which consisted of Basic Democracy members. He himself could not do this as a government servant. I had it printed secretly by a friend, Fazlur Rehman of Fazlisons. It had a thick black border, and the title, ‘Maut ka Muhaida’ (Pact of Death) with a Persian subtitle ‘Quame farokhtand wa che arzan farokhtand’ (How cheaply have they sold the country), and sent thousands of copies to BD members of Punjab and Sindh from different post offices in Karachi and Hyderabad, so that it could not be traced either to me or to Masud Saheb.

Another ICS officer, whom I met at my uncle’s house and became friendly with, was MH Zuberi, who lived in Islamabad near the Marriot Hotel where I stayed. Therefore in the evenings I used to walk over to his house. And when he retired he lived in Karachi in the street next to mine. Zuberi Saheb was in the habit in the evenings of walking over to my house to discuss his latest work. Later in the evening I would walk him back to his house. He wrote books on Abraham, Moses, Aristotle, Al-Ghazali and did a two-volume autobiography. Further as Secretary-General of RCD living in Tehran he had collected some rare Mughal coins.