Sindh

The name Sindh is derived from the Sanskrit word ‘Sindhu’ for a span of water, stream, river or ocean. The Sindhu of Sanskrit was pronounced Hindu or Hindus by Iranians and Indu or Indos by the Greeks, later becoming Hindustan to Asians and India to Europeans. The Arabs called the area they occupied up to Multan Sindh, to distinguish it from the rest, which they called Hind. During the Sultanate and Mughal period, the countries and provinces were known by the name of the family that ruled or its capital city.

Sindh was known as Meluhha during the Harappa period, Sangama in Ramyana, Sauvira, Sudra, Barbara in the Mahabharata, Hindush under the Achaemenian and Sassanians, as Indos, Prasania and Patalene under the Greeks, Shakadvipa under the Scythians, etc. During the early Hindu period Sindh was divided into and inhabited by Sindhus and Sauviras. Under the Arabs, Sindh was divided into Mansurah ruled by Banu Habbar, and Multan ruled by Banu Sama. This division was continued throughout the Muslim period, when Sindh was divided into Multan and Thatta suba.

Thatta first figured in history when Sultan Muhammad Shah Tughlaq, the greatest and one of the most learned kings of Delhi, arrived in Sindh in 1351 in pursuit of his rebel general Taghi who had taken refuge there. The sultan fell ill on 10 Muharram after breaking the Ashura fast with the famous Palla fish of Sindh. These are, according to local legend, found in abundance from January to April when they are on their way upstream to pay homage to the Darya Pir (Water Saint) Khwaja Khizr. The learned Sultan composed verses while he lay dying in his boat on the Indus at Sonda, about twenty-eight miles along the river from Thatta. The last couplet that he composed was,

‘I commanded all the pleasures that I wished

In the end I am bent like the new moon’

Thatta was difficult to conquer because it was protected on all sides by the waters of the Indus. A contemporary poet (Mutanhar Shah Kari) has described Thatta’s position in the following verse,

‘Thatta is an island, country full of caves

On its one side is a river (Darya) and on the other five waters (the Indus)’

Therefore when Sultan Firoze Shah Tughluq launched his second invasion of Thatta in October 1367, he came fully prepared for a long economic war, and told his nobles, ‘Where can this handful of Thattians fly to?…. My army shall remain here, and we will build a large city'.

The famine sapped the determination of the people of Thatta. Boatloads of people looking for food abandoned that place and began arriving at the imperial camp city, where the sultan had ordered the camp bazaar to sell grain at a subsidised price to all who came. In desperation, the Jams of Thatta sent messengers to their revered saint Makhdum Jalal al-Din Jahaniyan Jahangasht of Uchch, to intercede on their behalf with the sultan. An agreement was reached and the Samma ruling family arrived at the imperial camp to make their submission, with some being taken to Delhi and others being allowed to rule in Thatta.

Samma rule was effectively ended by Shah Shuja Beg Arghun, a descendent of the great conqueror Chingiz Khan and his Arghun viceroys of Iran., He defeated the Samma army outside Thatta on 11 Muharram 927/21 December 1520, and killed their hero, Mian Mubarak Darya Khan Doolla. The year of the conquest of Thatta by Shah Shuja Beg is obtained from the chronogram, ‘Kharabi-e-Sindh’ (Ruin of Sindh). When his son and ruler, Shah Hasan Arghun died on Monday 12 Rabi al-Awwal 962/4 February 1555, without a successor. Mirza Isa Khan Tarkhan, another descendent of the great conqueror Chingiz Khan, took over as ruler of Thatta.

The Tarkhan rule ended when Emperor Akbar of Delhi, a descendant of another great conqueror, Amir Timur (Tamerlane) sent his army under the command of Khan Khanan to conquer Thatta. Shaikh Faizi composed the chronogram ‘Qasad-i-Thatta’ (AH 999/AD 1590). Mirza Jani Beg Tarkhan met Khan Khanan on 1 November 1592, to surrender Thatta to the Timurid general. Thereafter Thatta was ruled by governors appointed by Timurid rulers of Delhi till Nadir Shah, the last great Asian conqueror, invaded India and under the treaty of 26 May 1739 annexed all the territory west of the Indus and the Hakra River. Thus after fifteen hundred years, Sindh once again became part of an Iranian Empire, and was cut off from the rest of India where the Mughal Empire, though it ceased to be an effective power, continued to provide the legal framework for Indian politics till AD 1857.

Ahmad Shah Durrani (AD 1747-1772) replaced Nadir Shah as ruler of the Indus Valley. He conferred the title of Shahnawaz Khan on Mian Nur Muhammad and extracted tribute from Sindh. Afghan rule over Sindh ended when the British took over Sindh and once again made it part of India. In 1842, Sir Charles Napier was posted as the British Resident in Sindh. He, like the Mughal general Khan Khanan before him, was an outright imperialist. He believed, as Khan Khanan had in 1590, that the situation in Central Asia required that Sindh and Afghanistan should be brought under imperial hegemony. Despite opposition from those in the company service who thought that Sindh would be a financial burden, Sir Charles decided to take over Sindh if the Talpurs refused to help them in their Afghan venture. The Khairpur Mirs agreed and were allowed to retain their state. The Hyderabad Mirs promised to sign a treaty but attacked and plundered the British camp and residency. Sir Charles moved his troops on 17 February 1843 to Miani, where the Hyderabad Mirs had stationed their troops, and defeated them. Sir Charles next moved against the Mirpur Talpurs whom he defeated at Dabbo. The armies of the Mirs were composed of Baloch, Pathans and their African slaves. The cry of Marsun Marsun Sindh na Desun was raised by an African officer employed by the Baloch Talpur governor of the Afghan king, fighting for Talpur, Baloch and Afghan possession of Sindh against a British army composed of Hindustanis and a few Sindhis officered by the British, who were out to establish traditional sub continental rule over Sindh usurped by the Afghans. It is therefore not surprising that today the old cry of, ‘Marsun Marsun Sindh na Desun’ is being raised by politicians of Baloch origin, and not by the Sammat of Sindh, in a language which is not even Sindhi.

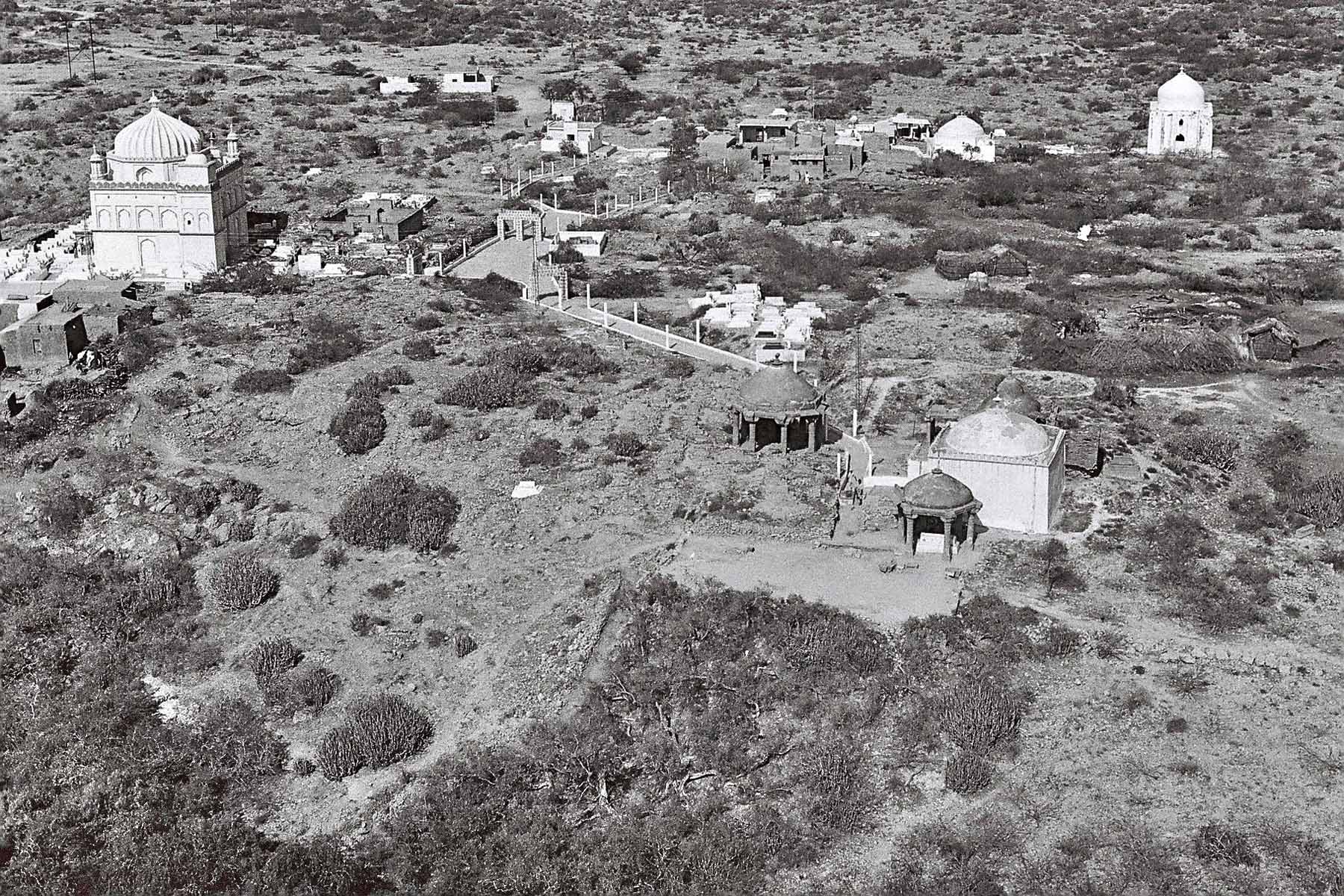

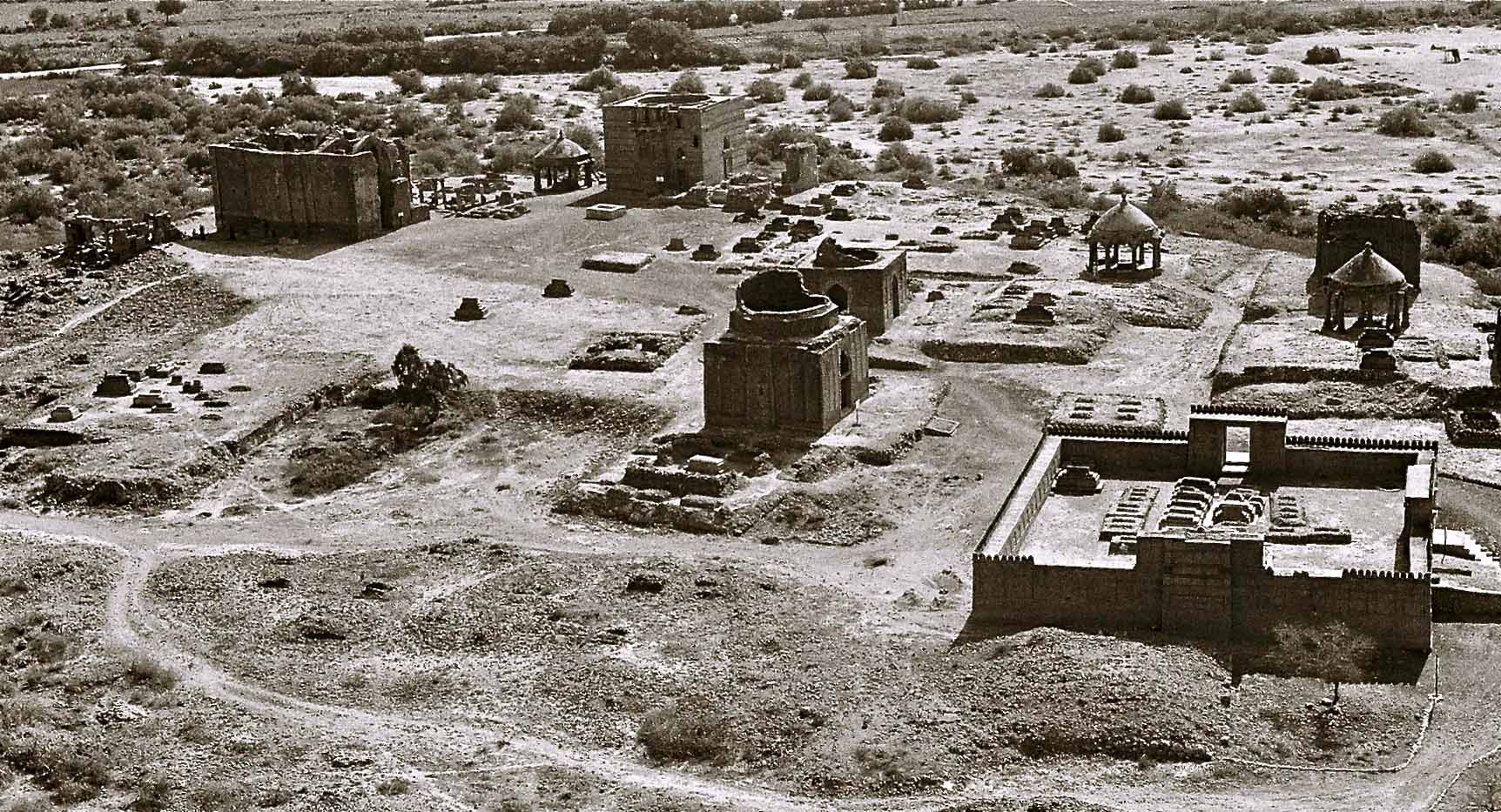

Alexander Hamilton who visited Thatta in AD 1699, wrote,’ Thatta is famous for Learning in Theology, Philology and Politicks, and they have above four hundred Colleges for training up Youth in those Parts of Learning’. But Thatta lost its political ascendancy, and Makli its architectural and spiritual hegemony in Sindh, as the Kalhoras from Baluchistan who were themselves religious leaders, established a new spiritual and political capital at Khudabad.

Another British visitor, Alexander Burns, who visited Thatta a hundred years later in the nineteenth century, wrote, ‘Its commercial prosperity passed away with the empire of Delhi, and its ruin has been completed since it fell under the iron despotism of the present rulers of Scinde. It does not contain a population of 15,000 souls; and of the houses scattered about its ruins, one half are destitute of inhabitants. It is said, that the dissensions between the last [Kalhora] and present [Talpur] dynasties, which led to Scinde being over-run by Afghans, terrified the merchants of the city, who fled at that time, and have no encouragement to return’

Our German friends helped us to document the traditional three-story mud buildings of Thatta with wind catchers, and my wife did a book on the vernacular architecture of Thatta. Our activity caught the attention of Mr. Badiuzzaman, Mayor of Thatta. He arrived to see what we were doing and expressed surprise, because he said that he did not know the value of the traditional mud architecture, and that he had been helping to demolish it. He said that in future he would try to convince people to maintain the traditional mud architecture. Although he is no more the Mayor of Thatta, he makes it a point to phone me every Eid from wherever he is.

It was hard work during the day, but pleasant in the evenings thanks to Akhlaque Hossain, CSP, who was head of the Sindh Sugar Mills Corporation, and had put us up at their rest house which had excellent rooms, food and table tennis tables. Akhlaque Hossain was an interesting person who believed in Jinns and in the efficacy of the Holy Quran in getting over calamities such as snakebite. He held a public park demonstration of a boy bitten by snake and in excruciating pain, while Akhlaque Hossain recited Surah Yasin from the Holy Quran to relieve him of his agony. I had Zohra Quraishi, editor/owner of She Magazine, with me, who was so affected that I had to take her away before she fainted.