Instant Islamic

Field Marshall Muhammad Ayub Khan, N.Pk., H.Pk., HJ, was the first military ruler of Pakistan. He took the capital away from Karachi to Rawalpindi, to be near the Army Headquarters, and began building Islamabad with the help of European and American architects. About half a dozen Pakistani architects were also invited to design houses for the government employees in Islamabad. They were Mazharul Islam from East Pakistan, and Allana, Bhamani, Mistri, Rustomjee, and Yasmeen Lari from West Pakistan. There Yasmeen Lari found that CDA was planning to insert arches and domes into the designs of western architects to make them Islamic. She coined the expression, “Instant Islamic” for it and protested.

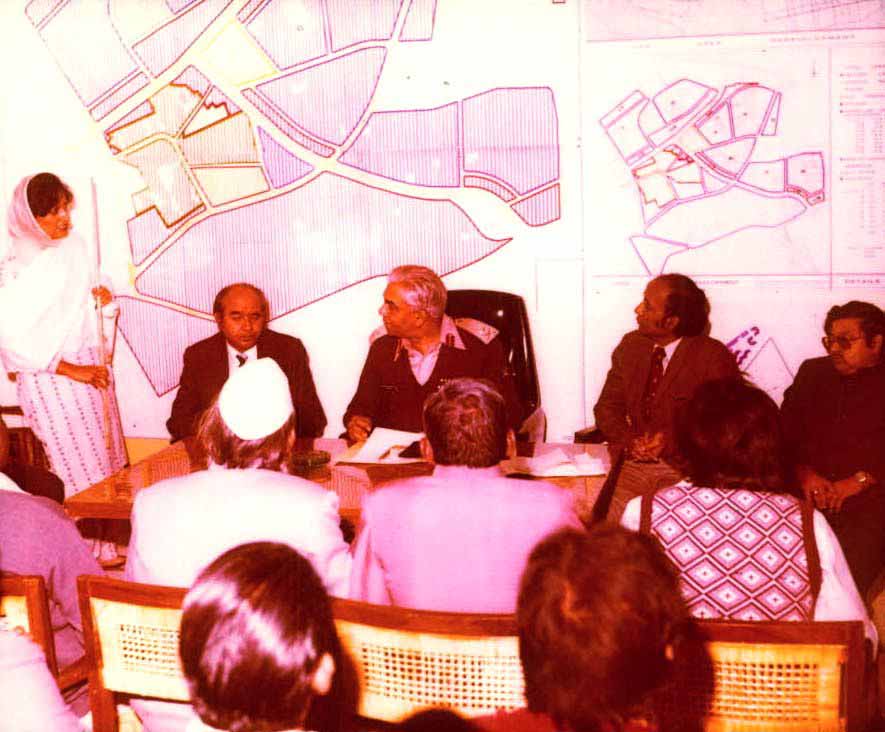

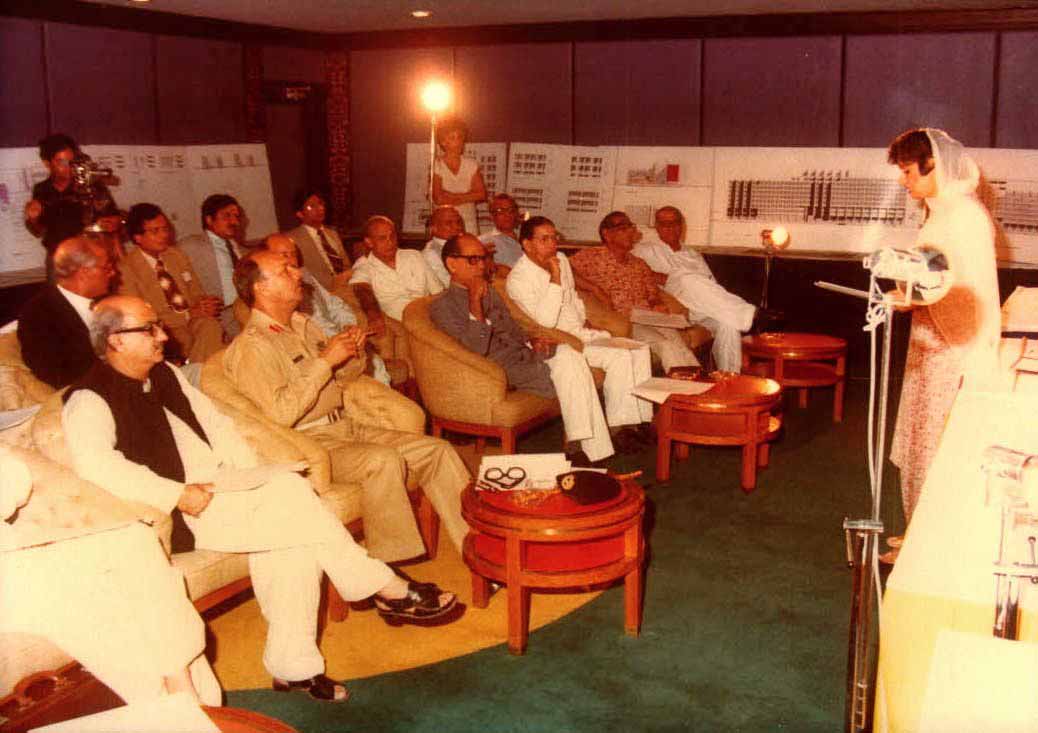

The Ayub government also convened conferences on Islamic Architecture in Islamabad and Dacca to make the architecture of the capital Islamabad and the second capital Dacca, Islamic. I had written an article titled, ‘Muslim but not Islamic Architecture’, for Karachi Artists Gallery whose thesis was that there was Muslim Architecture but no such thing as Islamic architecture. It was read by my wife at the conference, which created uproar, and she was criticized by both the administration and the Media. However, when the next conference was held in Dacca, she was applauded by the conference and media there. It is a great pity that her west Pakistani colleagues, architects and town planners at the conference did not support her.

Our thesis was that what we may describe as Islamic must be sanctioned either by the Quran or the Sunna of the Prophet (PBUH). This is the sine qua non of Islam. There are two sacred pieces of architecture mentioned in the Quran, Masjid-al-Haram and Masjid-al-Aksa. Neither of them had the mihrab, minaret, mimbar and dome, which are now popularly reputed to be Islamic. Further the Prophet’s (PBUH) mosque (Masjid-i-Nabwi), which he and his companions built with their bare hands in the first year of Hijri, was an enclosure of sun-dried mud bricks, each side being 56 yards long, with 10 feet high walls all around it. When his companions complained of being exposed to the rays of the sun while at prayer, a portico was built on the qibla side. This consisted of a number of palm trunks used as columns, supporting a roof of palm branches woven together and covered with mud. There was no mihrab, no minaret, no dome, no arch in the Prophet’s (PBUH) mosque (Masjid-i-Nabwi) the way the Prophet (PBUH) built it.

Secondly, there are those who define Muslim architecture in terms of certain features, namely the arch, vault and dome in secular and religious buildings, and the minaret, mimbar and mihrab in mosque architecture. Yet the arch, vault and dome are not typical of Islam, nor did Muslims invent them. The arch has been used since pre-historic times; Neolithic man spanned a wide opening by leaning together two stones in a triangular arch. The earliest known arches of a curved profile were built in the Tigris-Euphrates valley at least as early as 4,000 B.C. The Romans built triumphal arches commemorating their victories wherever they went. After the Byzantines developed the pendentive and the Sassanids the squinch, it was possible to construct a dome. The Persian fire temple and the Pantheon in Rome are the extant pre-Islamic examples of domical structures.

The first dome in Islam was the Dome of the Rock built in Jerusalem. Muqaddasi writes that Caliph Abdul Malik, noting the greatness and magnificence of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, was concerned lest it should move the minds of the Muslims. So the dome was erected above a rock, four hundred yards away from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and was patterned after the domical structure common to Roman mausoleums of the time, like the Pantheon in Rome built in A.D. 120.

During the Prophet’s (PBUH) time, as aforementioned there was no minaret in the Masjid-al-Nabawi. Hazrat Bilal was asked by the Prophet (PBUH) to give the call for prayers (azan) from the highest roof near the mosque. According to the Tabari, the azan was recited from an adjoining street or the city walls. The first minaret in Islam therefore had no religious significance. The fact that the minaret became a part of the mosque in a purely architectural way is clear from the account, which Ibn Faquih and Masudi give of their origin. Ibn Faquih says, “The minarets which are in the Damascus mosque were originally watchtowers in the Greek days. They were square and were known as the Syrian type of minarets. This type was taken to Cordova and Qairwan and remained the standard type in Western Islam until modern times.

The Prophet (PBUH) used to deliver his addresses leaning against a palm trunk fixed in the ground, until he had a mimbar made of tamarisk wood consisting of two steps and a seat. Hazrat Abu Bakr and Hazrat Umar never sat on the mimbar. They sat on the first and second steps leading to it. When Amr bin Aas at the mosque at Fustat wanted to set up a mimbar, Hazrat Umar forbade him, asking, “Is it not enough for thee to stand while Muslims sit at thy feet?”

According to Al-Suyuti, the mihrab was forbidden at the beginning of the second century of Hijri, as it was a feature found in churches, where it formed that part of the apse where images of Jesus and Mary were painted. The mihrab in the form of a niche was also a feature of the Greek and Hindu temples, where it was used to keep sculptures. The Muslims destroyed the sculptures and painted over the images, but soon carved new niches on the qibla side, which became known as mihrabs. These niches, baptized as mihrabs, ornament every Muslim building, tomb-stone, and prayer rug. Each Muslim head which bows in prayer to God also bows to a mihrab, carved on the qibla wall or drawn on a prayer rug. This is the extent to which we have transgressed from the simplicity of the Prophet’s (PBUH) days to the symbolic idolatry of today.

It is quite clear from the above account of the geneses of the arch, vault, dome, minaret, mimber and mihrab, that none of these features originated with the Muslims, nor were they condoned by them. On the contrary, they resisted them.

The term Muslim architecture is used in a third sense by those who say that whereas the architectural features mentioned above have not originated with them, they have become associated with Muslim architecture over the centuries, and as such it is correct today to describe Muslim architecture in terms of these features.

The first Muslims, who came out of Arabia to give the age a new creed, were a vital people. However, barely a few decades later they had become a nation of sycophants, who to please the caliphs, invented and conjured up thousands of Hadith. Therefore, in order to defend themselves against the encroachments of the rulers, the ulema devised the doctrine of taqlid.

This may have been a very clever way for the ulema to escape the impious sultans’ demands to sanction their activities through the invention of a new Hadith and new twists to Islam, but it also turned blind imitation into a religious virtue, from which Muslim thought never fully recovered. “Taqlid” literally meant the following of another’s opinion. It forbade deviation from the usual and from what was current. If the mosque at Medina had a dome, a minaret and a mihrab because the mosque as built by the Prophet (PBUH) had been demolished and, at a later stage, a new one built with all the paraphernalia of a standard mosque — mihrabs, minarets and domes — then one continued to build mosques with these features. Taqlid did not allow a person to go to the original sources in the life of the Prophet (PBUH) and the pious caliphs, since that would have been tantamount to ijtihad, the power of independent judgment. Muslim thought was thus ushered into an era of conformity from which it has yet to recover.