Allahabad

I was brought up in Allahabad, to which my father had moved to be near the High Court, and acquired a house with flower and vegetable gardens and fruit trees including mango, guava, sita phal, kathal, molsery, holy bael and mahua. The house had its traditional churail, a harmless and restless soul in a white sari who wandered around our beds at night as we slept under the summer sky and saw the falling stars, as the angels protecting God in the seventh heaven would throw them at the devil, to keep him at a distance from the Almighty. We were told that she was the ghost of a previous lady of the house who had committed suicide. Also, our property was large enough to have a badminton court for the female members of the family and a hockey ground for boys.

Allahabad, or Prayaga (place of offering) is considered one of the holiest places in the Hindu religion, where after creating the world, Brahma offered his first sacrifice. In the sacred Vedic literatures, it is situated at the confluence of three sacred rivers, the Triveni Sangam, where the Jamuna and the invisible Saraswati, which flows underground, meets the Ganges, which then takes off to meet another great river, the Brahmaputra (Jamuna of Bengal).

The legend is that the gods thought of churning the Ksheera Sagara (the primordial ocean of milk) to obtain amrita (the nectar of immortality). This required them to come to an agreement with the demons or asuras to work together. However, when the kumbha (urn) containing the amrita appeared, a fight ensued for its possession. For twelve days and twelve nights (equivalent to twelve human years) the gods and demons fought in the sky for the pot of amrita. During the battle, the celestial bird, the Garuda, the vehicle of Vishnu, flew away with this kumbha of elixir, and drops of amrita fell at four places on earth: Prayaga (Allahabad) and the Haridwar (Hardwar) in the U.P., Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh and Nashik in Maharashtra. In memorium, the Kumbh Mela takes place at Allahabad every three years, and the Ardh (half) Kumbh Mela is celebrated every six years, while the Purna (complete) Kumbh takes place every twelve years. The Maha Kumbh Mela comes after every 144 years. I often joined the pilgrims going to sangam as they passed in front of our house.

The Timurid Emperor Akbar visited it in 1575 and named it Illahabas (Abode of Gods) and ordered a fort to be built. It has the Ashoka Pillar that was erected by the order of the great Mauryan king in 232 BC, with inscriptions in Brahmi, Gupta and Arabic scripts by three great emperors of three religions, Buddhist Ashoka, Hindu Samudragupta and Muslim Jahangir.

It was Saleem’s (later Emperor Jahangir’s) capital when he rebelled against his father Emperor Akbar, and had his name read in Friday prayers and his name minted on coins. It holds the three exquisite tombs of Jahangir’s wife, son and daughter in the garden named after his son, Khusrau, who had rebelled against him and was blinded. Khusrau Bagh is famous for its guavas. It possesses one of the first high courts built in British India, and one of the oldest British universities in India, known as ‘the Oxford of the East’, where my uncle Zafarul Ahsan Lari, ICS, studied, taught English literature and wrote short stories. Aftab Ahmed Khan, ICS, told me that as a student of his when he read one of his essays to him he told him that I would be selected for ICS this year and that he would follow him. Allahabad is associated with seven prime ministers of Independent India.

Our house, number 26, was the last house on Hamilton Road where most of the famous lawyers lived, and in the evening came out to stroll with their ladies in their starched flowing white dhotis and saris, which reminded one of Krishan Chandar’s story ‘sau gaz lambi sarak’. It had only one other Muslim House, which was next to ours, and therefore the other twenty boys who made up two teams to play hockey in the evening at our house must have been non-Muslims despite my father being a Muslim League leader. I remember that my Muslim neighbour Kamal Mansur Alam, who later became Chief Justice of Sindh and a judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, had hit me so hard while playing hockey that my right ankle remains swollen to this day, while the left leg has the scar of being cut by a bike on which I was travelling with Azhar uncle in Allahabad.

Hindu students were in the majority in school, and although we had a PT and sports period every day, where intensive physical interaction took place in all kinds of sports and athletics, I only remember the Muslim boys who played with us. The same was the case in the class where the Muslim boys sat together, and I only remember some of them. There was an exception to this when a Hindu refugee boy named Prem came from Punjab, joined the Urdu class and excelled. This was a surprise, because till then the Urdu class did not have any Hindu students, as all our Hindu classmates had opted for Hindi.

Our large servants’ quarters housed one Shuder/Dalit family with a lot of children, one Brahman husband and wife, a Maulvi Sahib and his wife, who was supposed to make sure that we said our prayers. There were also orphan boys and girls who came from our village to work and live with us, and one of them died of smallpox. I only remember the Brahman family, because whenever we accidently touched the Brahman lady while playing she immediately stood under the communal shower in the compound to drop water over her head to purify herself symbolically. She also showed great displeasure if our ball went into her quarter, as our hockey ground was sandwiched between the kitchen quarters and the servants’ quarters.

Our house was the centre of Muslim League politics in Allahabad. My elder sister, Bilquis Jamal, wrote short stories for the Urdu magazine Nighat of Allahabad, and organised demonstrations in girls’ schools and colleges for the Muslim League. The boys’ wing of the Muslim League was led by Salahuddin Aslam, who worked day and night for the Muslim League. As a result his studies suffered, so he ended up being a photographer for a newspaper in Karachi, organized the Pakistan Association of Press Photographers and was elected secretary of the Karachi Union of Journalists. However, the student who was instrumental in establishing the Muslim League Student organisation in Allahabad was Mukhtar Zaman, with his associates Zuhair Siddiqui, Shah Mahmood Sulaiman, and many others. Mukhtar Zaman was general secretary of the All India Muslim League Students’ Federation, with Raja Saheb of Mahmoodabad as its president, and had a long and distinguished career as a journalist and a writer. An interesting member of the student movement in Allahabad was Saleem Akhtar, who later became a judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. The most colourful character was Kunwar Tehsin Yunus Ali Khan, who suffered injuries in a fight with Hindu boys for his provocative demeanour and colourful language, which he maintained even in Karachi as a customs officer. When his father admonished him for receiving a knife wound on his back, his answer was that it was not him but those who attacked him who were cowards, because they dared not attack him from the front. I was therefore surprised when Salman Faruqui went to a conference in Delhi, and his counterpart in India, a Hindu, asked him about me and gave Salman’s wife his phone number so that I could contact him.

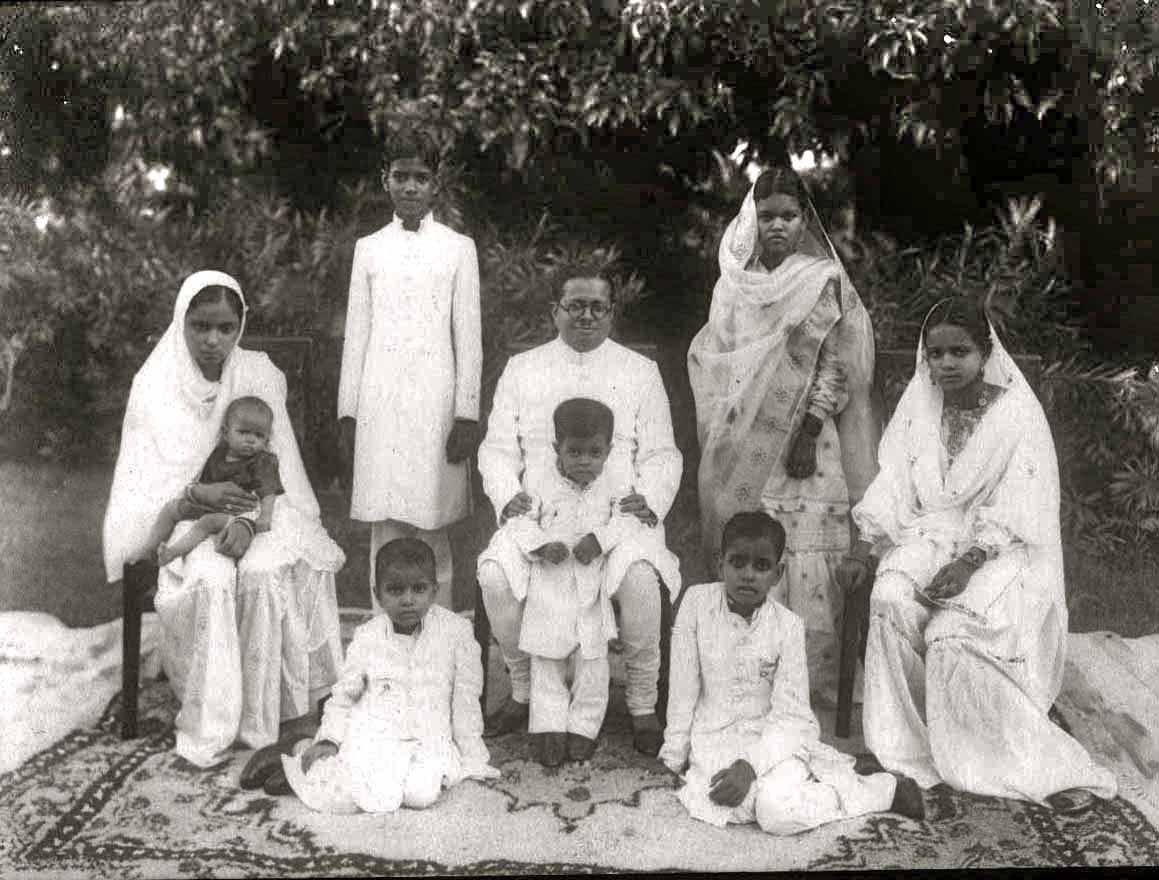

As Deputy Leader of the Muslim League Assembly Party in the U.P. Legislative Assembly, Secretary of the U.P. Muslim League Parliamentary Board, and later as Leader of the Opposition and member of Constituent Assembly of India, my father was mostly away touring the countryside in his Ford car. We often followed him to Muslim League gatherings as audience and slogan raisers, and during the long summer school holidays our mother took us to Naini Tal Hill Resort, where the U.P. Legislative Assembly held its summer session.

Allahabad was visited by all the top Muslim League leaders, for whom special meetings were arranged. We now laugh at the fact that though the Quaid spoke in English, even the youngest and most uneducated of the Muslim audience thought that they understood him and cheered him on. We were often taken care of by a colleague of my father, Shaukat Ali Khan, MLA, who did not have children of his own and gave us long lectures on every subject that affected Muslims. Our favourite Muslim League leader was Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar, who warned Hindus not to mistreat the Muslims of minority provinces, because Pathans knew how to avenge their brothers. He said, ‘I can take one Hindu in one hand and another in the other and smash their heads together’. It reminded us of Emperor Babar who is supposed to have run on the fort wall with one Hindu under one arm and a second under his other, and used to throw them over the wall to their death. It was this kind of statement and story which intensified enmity between communities.

My father’s main contribution to our upbringing was in the provision of books. He had a large library and he allowed us to buy books by signing for them at Kitabistan bookshop, whose owner was instructed to send the bill to him. For this I was often told off because my elder sister quite often bought popular novels from the shop and made me sign for them, which my father did not like. This is a tradition, which I kept up with my own children, who were also allowed to buy books by signing for them at the Pak Amerian Bookshop on Elphinstone/Zaibunnisa Street in Karachi. One of my favourite books from my father’s library was a two-volume set of the complete plays and prefaces of George Bernard Shaw, in which he said something to the effect that if we wanted to understand his life work then we should read it twice every year for the next ten years. I followed his advice for a number of years.

As children we were brought up on Alif Laila and Dastan-i-Amir Hamza. My mother subscribed to “Ismet” magazine from Delhi, and a number of children’s magazines from Lahore, like “Phool” and “Khilauna” for us, while the Urdu newspaper “Madina” from Bijnor and the magazine “Nigar” of Niaz Fatehpuri from Lucknow came by post. Articles by Niaz were often provocative and created intense debate.

At school, Tegh Allahabadi became an instant hit with his revolutionary poetry at the annual swadeshi numaish of Allahabad. When he moved to Pakistan he changed to his real name, which was Mustafa Zaidi (1930-1970), passed the civil service exam and became a bureaucrat till he was screened out by martial law government. This depressed him so much that he made a suicide pact in which he died but the lady survived and a case was registered against her. I met her at Karachi Gymkhana with her lawyer Mr. Farooqui where they were regulars on the dance floor. The lady lived near us on 3rd Gizri street while we lived on 4th Gizri street in DHA-4 in Karachi, and after her husband died she brought one of her daughters to me to work with us for the Heritage Foundation. She was a kind and petite woman with beautiful eyes, who wrote to the newspapers that the Kohinoor diamond in the British crown had been taken from her family by deceit by Maharaja Ranjit Singh, and that therefore the British should return it to her. I reproduce here a verse from each of five poems that Mustafa Zaidi published in her name:

Lay chali thi mujhay zarron ki tarah bad-e-samoom

Tu nay hiron ki tarah mujh ko sanbhala rakha

Apni palkon main chupaya mujhay tunay us waqt

Jab saray rah har aik fard mera qatil tha

Mayn alag ho kay likhun teri kahani kaisay

Mera fan mera sukhan mera qalam tujh say hay

Duniya main aik sal ki muddat ka qurb tha

Dil main kaiy hazar qiran ki sharik thi

Shairo, Naghma garo, sang tarasho, dekho

Us say mil lo to batana kay hasin tha koi